×

The Standard e-Paper

Home To Bold Columnists

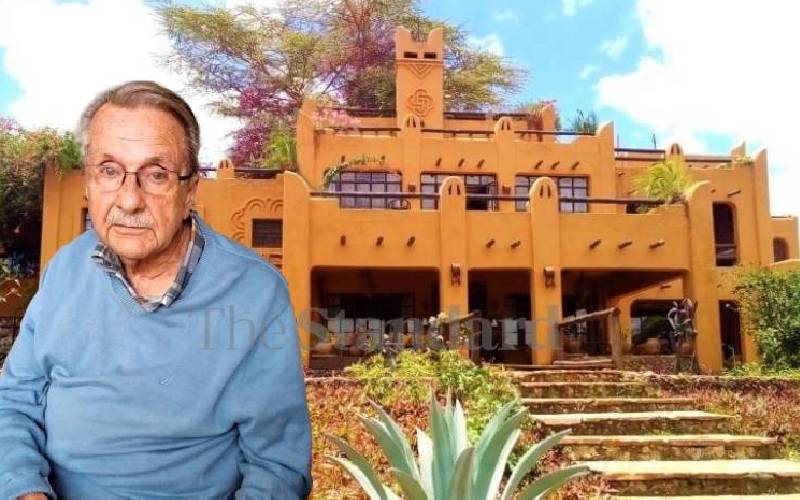

The African Heritage House, in Mlolongo, Nairobi, was designed by Alan Donovan. [Gilbert Otieno, Standard]

It is late 1969. A second-hand Volkswagen Combi hurtles through the Sahara, braving the blinding sands around Timbuktu and the gusty winds of Djenne in Mali.