×

The Standard e-Paper

Fearless, Trusted News

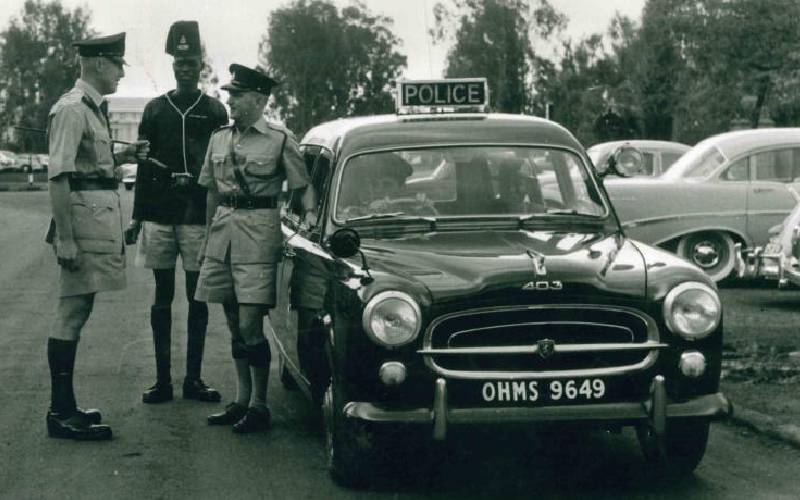

Colonial traffic police officers, 1960s. [File, Standard]

The British settlers and other nationalities left their footprints in Kenya in terms of big houses that dot the once white highlands.