×

The Standard e-Paper

Smart Minds Choose Us

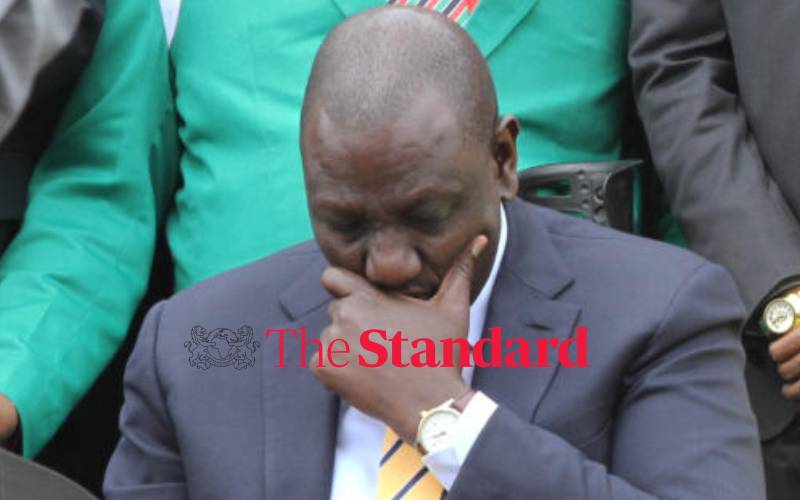

Deputy President William Ruto. August 5, 2021. [Elvis Ogina, Standard]

The Court of Appeal upheld the illegality of the constitutional review process launched by President Uhuru Kenyatta and opposition chief Raila Odinga.