×

The Standard e-Paper

Kenya’s Boldest Voice

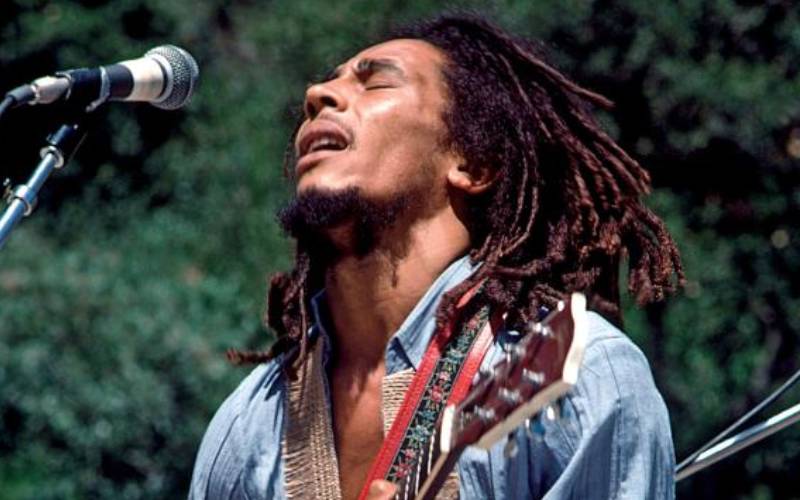

Reggae icon Bob Marley. Reggae music has been hijacked by politicians as part of that cultural cocktail. [Courtesy]

International Reggae Day was on Thursday, a day to the conclusion of the appeal hearing of the BBI (Building Bridges Initiative) before a seven-judge bench at the Court of Appeal.