×

The Standard e-Paper

Smart Minds Choose Us

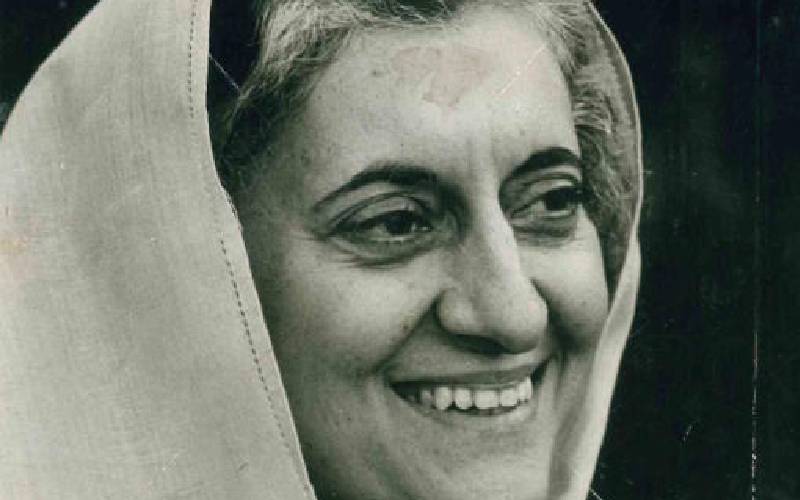

Former Prime Minister of India Indira Gandhi. [Courtesy]

When it met at the Constitution Hall in New Delhi on January 24, 1950, to vote for the constitution, the Constituent Assembly for India resolved to establish a socialist state.