×

The Standard e-Paper

Home To Bold Columnists

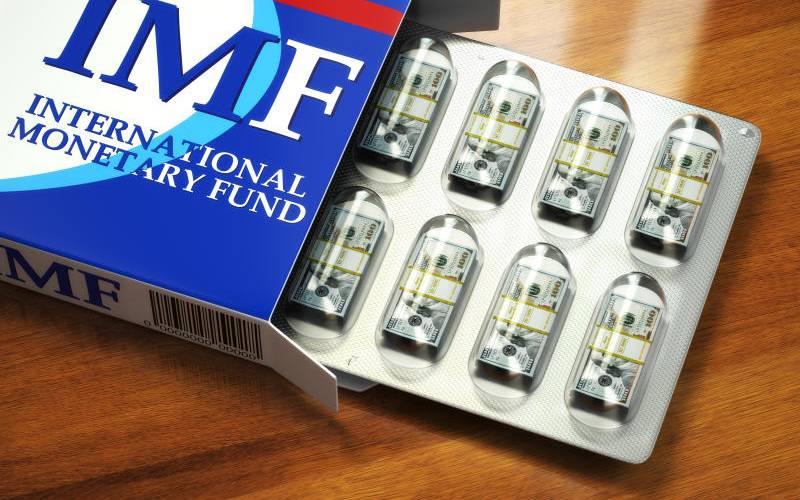

Concept of IMF tranche.

In recent years, Kenyans have wrestled to take away the bitter chalice associated with high public debt. Pundits have analysed the economic effects of rising debt and the public has debated the moral contours of the high taxation regime required to sustain it.