×

The Standard e-Paper

Stay Informed, Even Offline

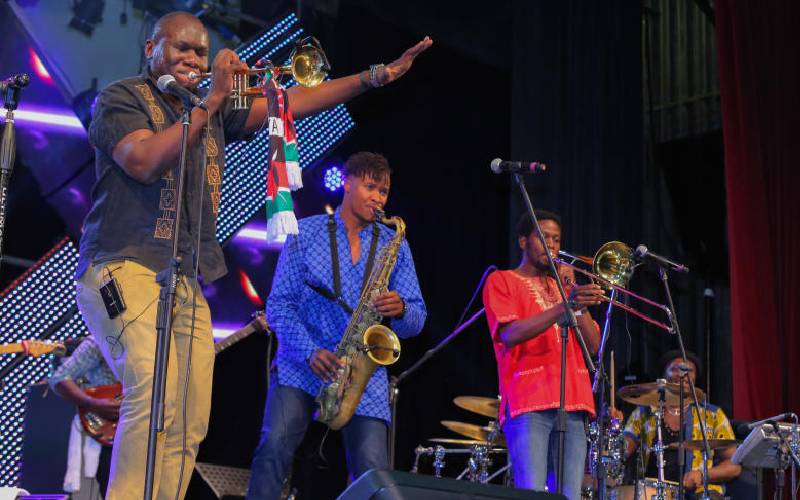

At one time, while working his 8 to 5 job, Nairobi Horns Project founder, MacKinlay Musembi was thinking about his life.

He had just watched Apple founder Steve Jobs say that he lived every day like it was his last.