×

The Standard e-Paper

Smart Minds Choose Us

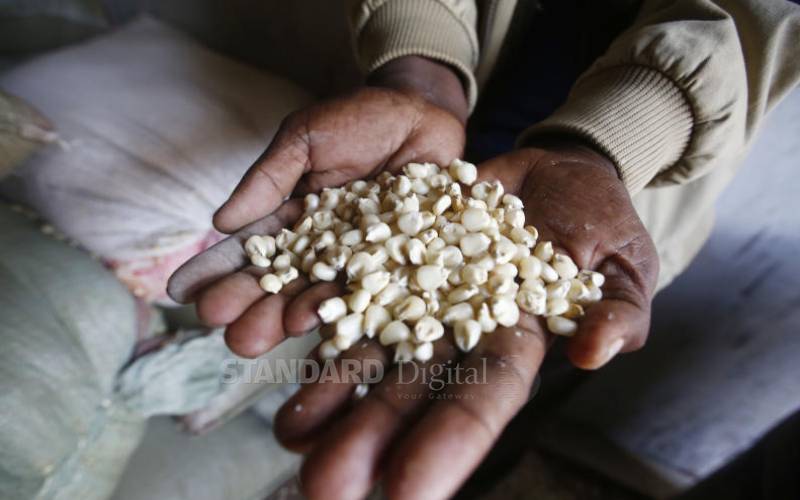

Efforts to control aflatoxin in Kenya mostly focus on testing maize once it reaches our borders, or once it hits supermarket shelves.

Enforcement of food safety regulations is necessary but insufficient to solve this problem. Aflatoxin contamination must be addressed at its root, during production and on-farm storage.