In his award-winning seminal essay, ‘The worst mistake in the history of the human race’, Jared Diamond argued that in transiting from hunting-and-gathering to agriculture-based production, humans committed their most cardinal error. He points out that “with agriculture came the gross social and sexual inequalities, diseases despotism and injustice that curse our existence.”

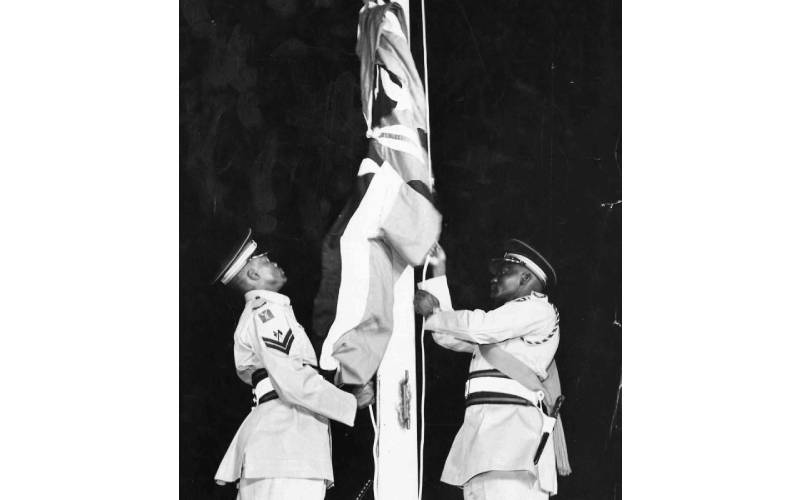

We make a similar considered claim which some might find preposterous: That the worst mistake that ever happened to Kenya is when she obtained independence in 1963. Many contemporary scholarly viewpoints insist that in Africa, colonial rule indeed brought great improvements in economic development, long-term health and well-being, and that, without any plausible counterfactual evidence, Africa is poorer today than when it was colonised.