×

The Standard e-Paper

Kenya’s Boldest Voice

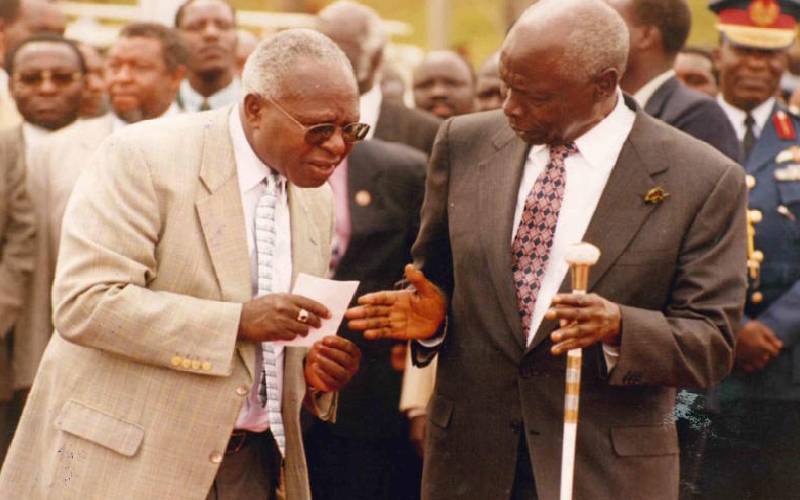

President Moi and Finance minister Simeon Nyachae on September 30, 1998. [File, Standard]

In 1979, President Moi promoted Simeon Nyachae to the permanent secretary in the Office of the President, with the responsibility of coordinating development projects and organising information for the Cabinet. In July 1984, consequently, Nyachae was the logical successor to Jeremiah Kiereini as chief secretary and Head of the Civil Service.