×

The Standard e-Paper

Fearless, Trusted News

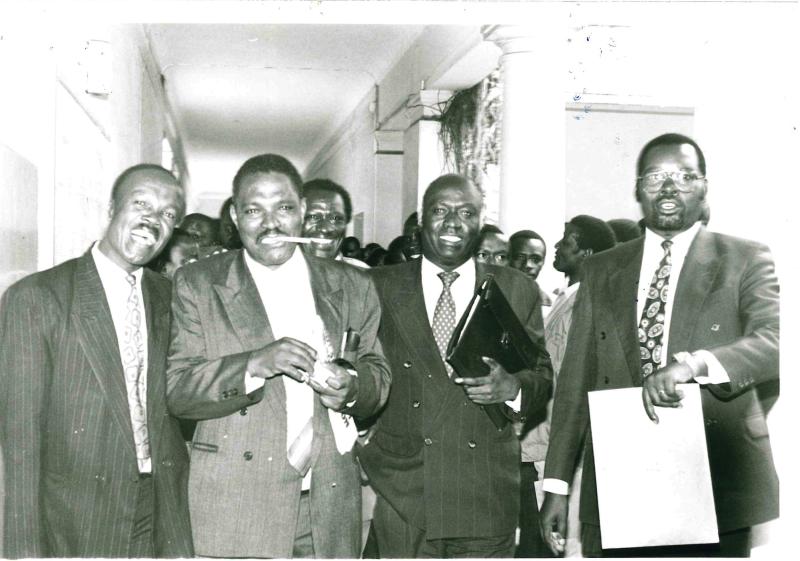

John King’ori (second left) with his supporters outside the High Court in 1994. [File, Courtesy]

John King’ori Mwangi, colourful former Nairobi mayor, died last week. For years, King’ori was the epitome of what defined leadership in the capital.