×

The Standard e-Paper

Join Thousands Daily

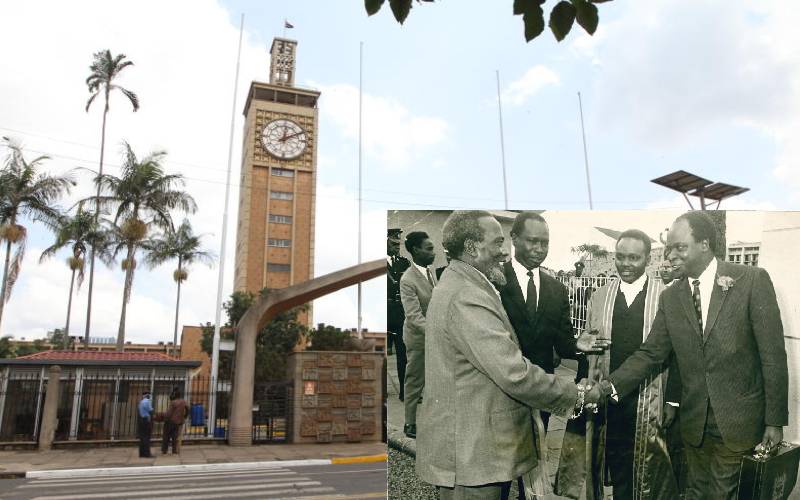

Then Finance Minister Mwai Kibaki with his bosses Jomo Kenyatta and Daniel Moi at Parliament Buildings in 1971. [File]

Occasionally, one catches flashes of brilliance on the floor of parliament, especially in the Senate where battle-scarred political generals and masters of rhetoric tango in a game of wits.