×

The Standard e-Paper

Fearless, Trusted News

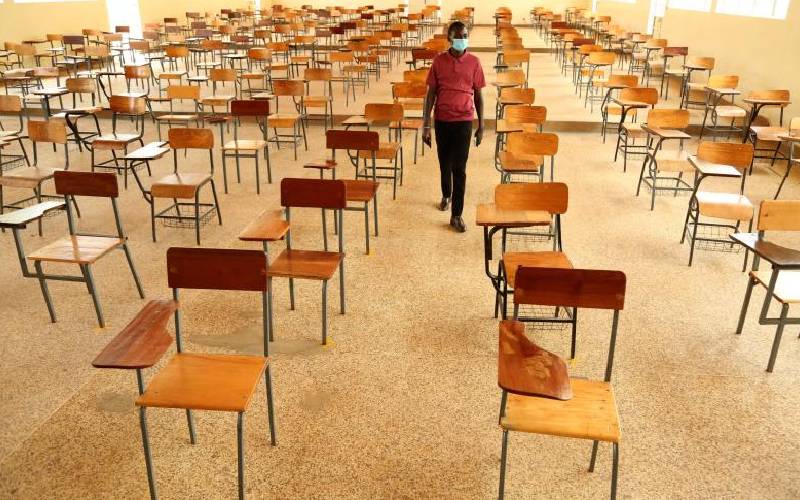

A student walks inside a lecture hall at Maseno University after universities reopened countrywide on October 5, 2020. [Collins Oduor, Standard]

Universities, like any other social institutions, have had to face devastating epidemics that have impacted their daily functioning. And they have survived and continued their mission even with their doors closed.