×

The Standard e-Paper

Join Thousands Daily

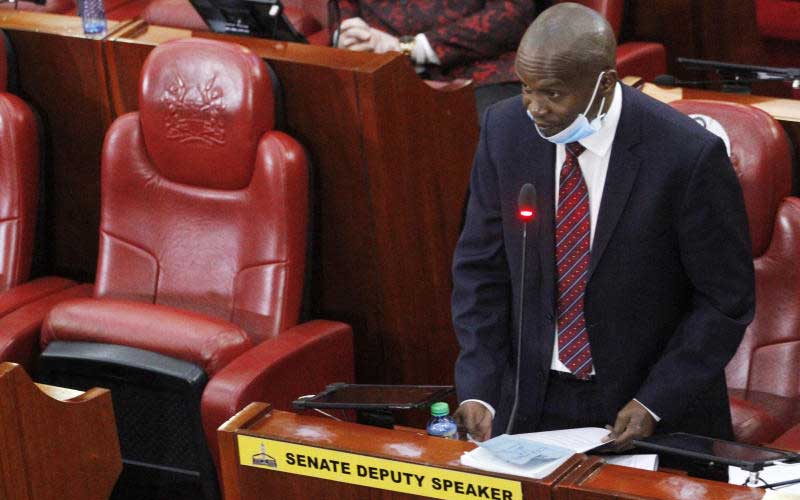

Tharaka Nithi Senator Kithure Kindiki when he was ousted as deputy speaker of the Senate on May 22 over allegations of disloyalty to the party. [File, Standard]

The liberty to make political choices, including the right to form and/or participate in the activities of a political party, is well enshrined in the Constitution. In order to give effect to this constitutional provision, Parliament duly enacted the Political Parties Act in 2011.