×

The Standard e-Paper

Stay Informed, Even Offline

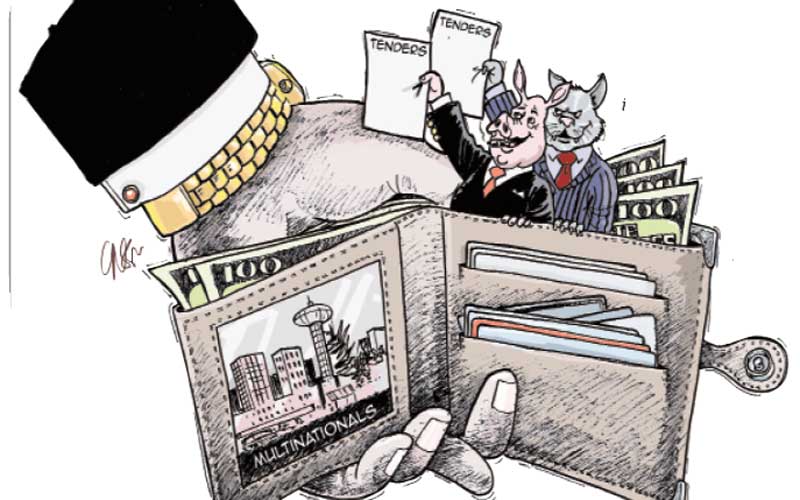

Kenyans often lament that 'Kenya’s problem is not that we don’t have good policies and plans; our problem is we don’t implement them'. But that makes the solution to the corruption problem seem trivial.