×

The Standard e-Paper

Kenya’s Boldest Voice

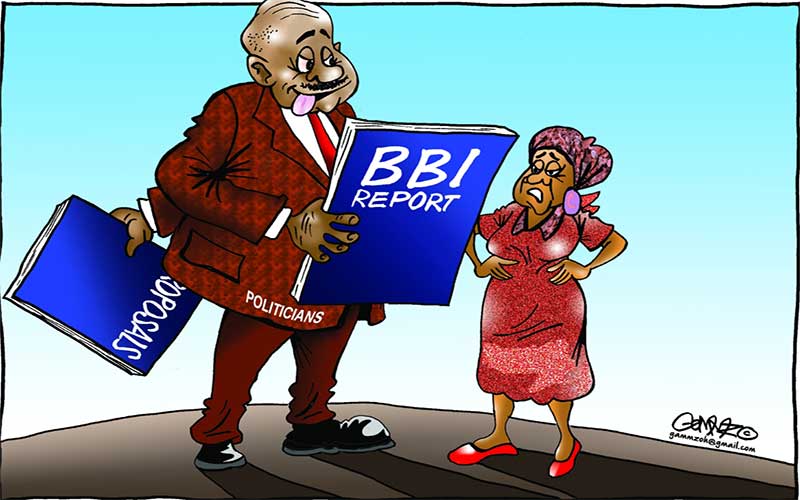

The trigger for the Building Bridges Initiative (BBI) was the disputed results in the 2017 presidential elections, the third in a row. The first disputed results, in 2007, triggered a major political crisis that needed international mediation. That mediation yielded a programme of far-reaching electoral reforms, calculated to prevent future electoral violence.