×

The Standard e-Paper

Smart Minds Choose Us

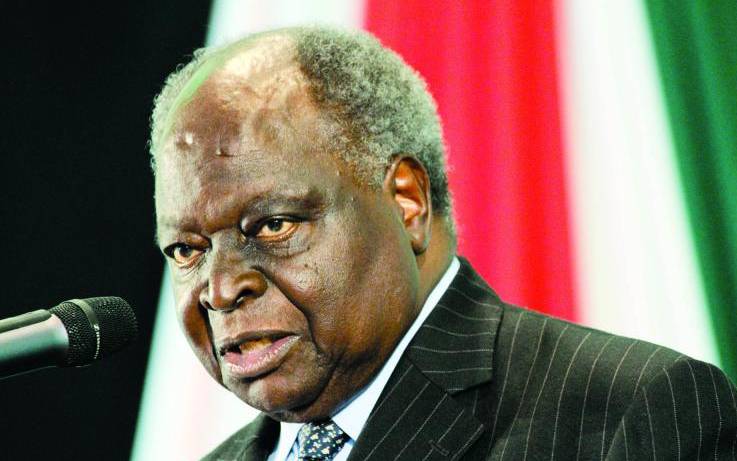

One of the things former President Mwai Kibaki (pictured) is remembered for is the Free Primary Education (FPE) he introduced after taking power following the 2002 General Election.