×

The Standard e-Paper

Smart Minds Choose Us

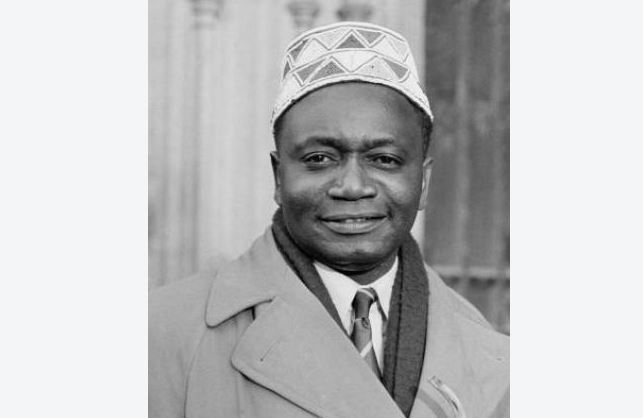

A pre-independence plot by the British to force Coast independence hero and KADU leader Ronald Ngala to work with KANU’s Tom Mboya would have changed the course of Kenya’s history had it gone through.

Revelations in Keith Kyle’s The politics of the independence of Kenya show the grand plans the departing colonisers had for the two men whom they considered “golden men” moderates who could steer Kenya to a more glorious future than their comrades.