×

The Standard e-Paper

Smart Minds Choose Us

Since the census numbers for 2019 run the risk of political hijacking, the onus is on the KNBS to think beyond the census.

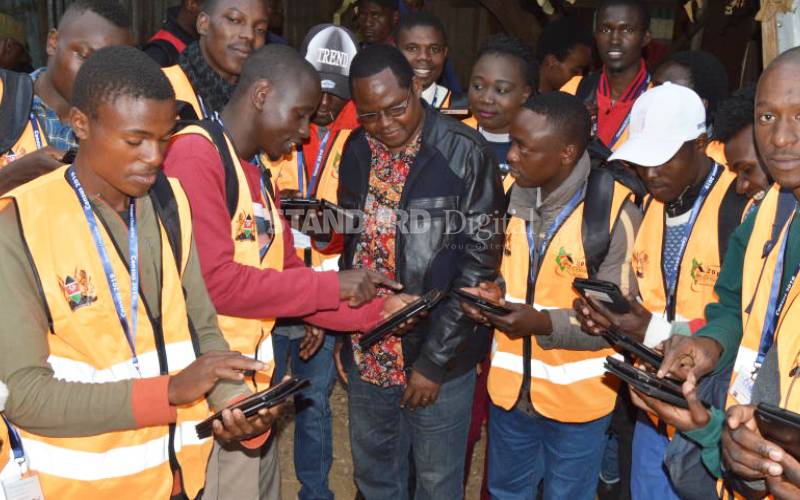

Even before the chalk digits that census enumerators imprint outside of households fade, it is emerging that the 2019 census may be tainted with political posturing to an extent the final results may well not serve their purpose.