×

The Standard e-Paper

Fearless, Trusted News

There is no failure. Only feedback- Robert Allen

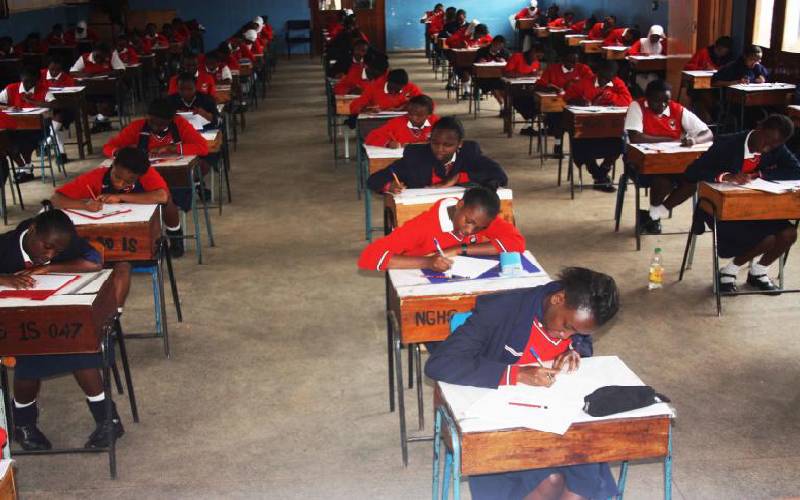

Some principals often tell parents and other stakeholders during secondary school functions that their school is privileged to have some members of staff who mark national examinations.