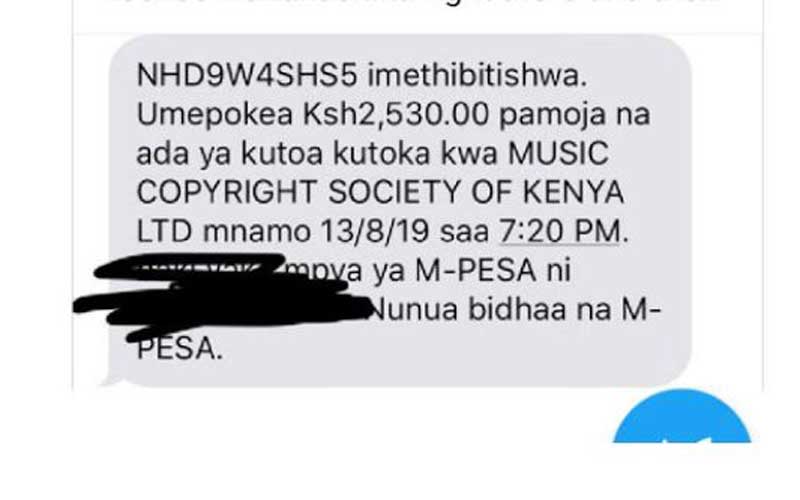

In the past few weeks there has been a raging debate about the entire system of royalty management since the music Collecting Societies’; Kenya Association of Music Producers (KAMP), Performers Rights Society Kenya (PRISK) and Music Copyright Society of Kenya (MCSK) distributed their royalties.

Some artists have accused the Collecting Societies, also referred to as Collective Management Organisations (CMOs), of inefficiency and failing in their mandate. Others have accused them of corruption. Some members of the public have even wondered if these societies should exist; questioning whether they are legally recognised.