×

The Standard e-Paper

Home To Bold Columnists

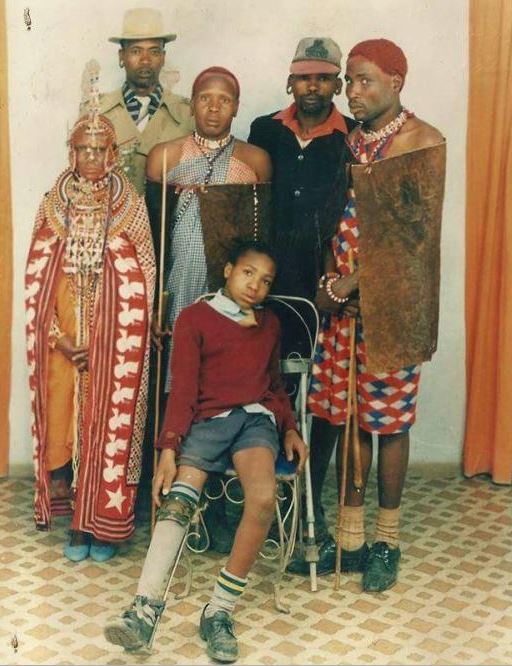

"I lost the use of my legs at the age of 12. The moment the doctor announced I’d be handicapped for life, everything changed. I had to rethink my future,” says 40-year-old David ole Sankok. “I’d wanted to become a cattle rustler; it was the only thing I knew. Without my legs, this would never be possible. I was devastated at the time, but chose to change my path.”

Ole Sankok, 40, a multi-faceted entrepreneur, runs a thriving farm and resort in Narok and is a nominated member of Parliament. He shares his story with Hustle.