×

The Standard e-Paper

Kenya’s Boldest Voice

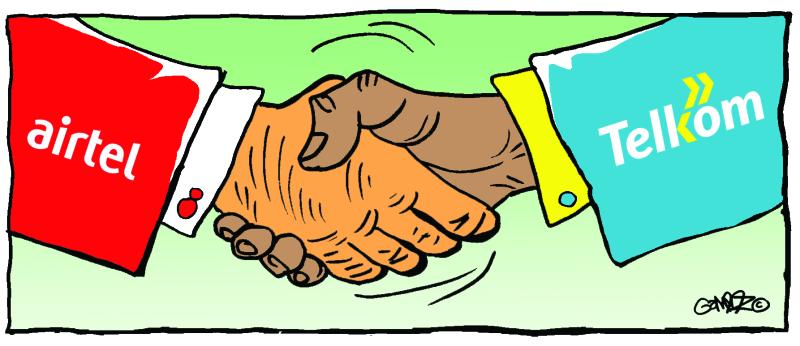

The confirmation of the union of Airtel Kenya and Telkom may have excited the market on Friday but a closer look reveals the future might not be so rosy for the two firms, their consumers and to an extent the industry.

The last time a deal of this magnitude was struck in the country’s telecommunications sector was in 2014 when Safaricom and Airtel agreed to snap up Essar Telecom.