×

The Standard e-Paper

Smart Minds Choose Us

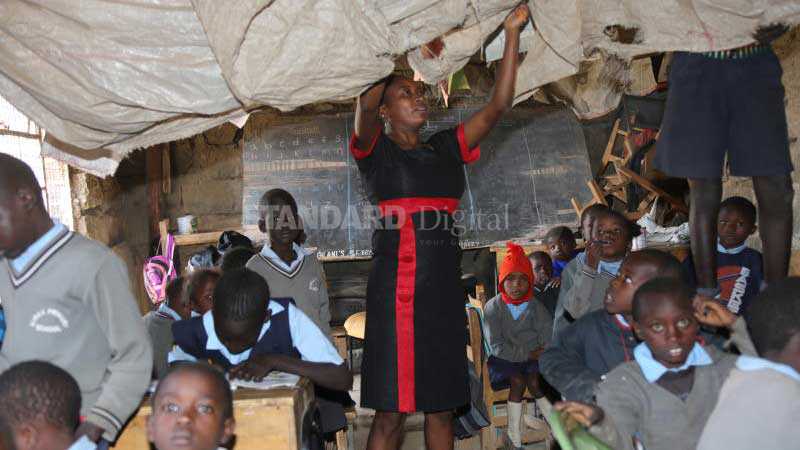

Since John Owalo, the separatist African church clergyman, established the first genuine community self-help schools in Kenya over 100 years ago to provide western education, different shades of self-help movement have emerged.

While Mr Owalo and his colleagues in the African independent church leadership concentrated their educational efforts on religious self-determination, other groups pushed for independent western education that would guarantee preservation of ethnic cultural identity.