Kenyans must now get ready to survive on shoe-string budgets as the expected rise in pump prices threaten to push up the cost of living.

In coming months, consumers will pay more for food, transport and electricity — all heavily dependent on oil — as the pace of inflation hits households.

Already, there are telling signs of hard times ahead with recent inflation figures reflecting a surge in consumer price index. From the latest figures from the Kenya National Bureau of Statistics, inflation accelerated for the third straight month to a nine-month high of 6.68 driven by increase in prices of most food items.

The shilling has also lately weakened as the uncertainty in the economy grows ahead of the next year’s election. All these are conspiring to spell economic doom.

The Nairobi Securities Exchange (NSE) has been the first causality of the lean times.

Most of the listed firms are bleeding after foreign investors pulled out for safer havens. In the last four months, only six companies of the more than sixty have registered slight gains in their share pricing and shareholders’ wealth has been wiped out.

Discounted prices

In the past two years, Kenyans enjoyed discounted fuel prices that cushioned them, but this is about to come to an end. The expected fuel price rise, analysts warn, would send shockwaves across the various economic sectors.

Silha Rasugu, an analyst at Equity Investment Bank said resurgent of prices will destroy a good run, unmasking the under-performance of the exports and the entire economy. “We might not see an immediate impact, but with time, if the rally continues, we will see a deficit in our balance of payments considering that the oil makes up a quarter of all our imports,” he said.

According to the Kenya Economic Survey 2016, the country spent Sh 226.1 billion on petroleum imports. This was substantially lower than Sh 335.7 billion, which was the billing in 2014 and Sh 321.9 billion in 2011 when crude prices were above $100 per barrel.

The difference of Sh 129.6 billion spending is expected to filter into the prices of the various consumers products in terms of price increase to cover the inflated import cost for fuel expected in the coming months.

For consumers, if the rise is sustained, it could mean the last of the low oil prices at the pump and an end to lower cost of living.

Already, for the first time in 16 months, a barrel of crude oil had gone above $50 (Sh 5,085) to sell at $51.35 (Sh 5,225) condemning kerosene and petrol prices to rise by Sh 3.45 and Sh 3.38 respectively.

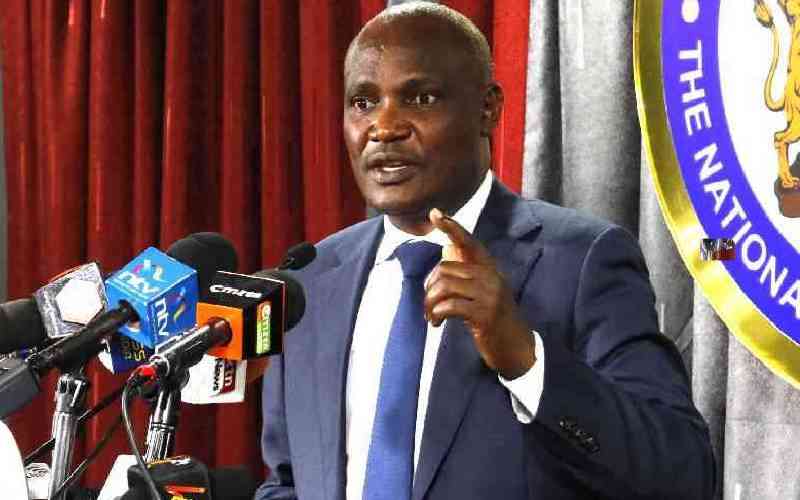

According to Energy Regulatory Commission (ERC) Director General Joseph Ng’ang’a, the prices are likely to go up in subsequent pricing line with this increase as well as performance of the shilling.

“The issue has been that OPEC was not agreeing on the level of output but now that together with non-OPEC members like Russia, they have brokered a deal, the prices will go up. Inevitably, local prices will start going up,” he said.

Stay informed. Subscribe to our newsletter

A lot is at stake for Kenyan consumers after Wednesday’s last week OPEC agreement in Vienna to cut production and bring an end to cheap fuel.

For Kenya, the oil bill used up more than a quarter of Kenya’s import bill when prices were above the $100 mark. And a return to this high prices spells doom to the entire economy.

For eight years, Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) have treated each other with skepticism. But the largest oil producers have finally agreed to put all the cards on the table and unify the rules of the game.

And even before they left the table, the decision by OPEC to drain the global oversupply has sent prices of crude oil soaring.

Biggest increase

Oil prices have been on an upward trend since the deal was brokered, reaching $53.50 by Friday. According to a Reuters report, the increase in prices last week was the biggest weekly rally since 2009.

OPEC members are expected to cut production by about 1.2 million barrels a day to 32.5 million. Russia, a key non-member producer will also reduce its production by 300,000 barrels by next year. It is expected that the deal will bring global oil supply and demand back into balance early in 2017.

This could have an impact on Kenya, which, while still hopeful of being an oil producer, is still a net importer of petroleum products.

In 2011, crude oil markets sustained high price levels with spot price of Brent averaging $111.26 per barrel- the first time the global benchmark averaged more than $100 per barrel for a year.

And locally, the impact was huge. From April of the same year, inflation hit double digit rising to an all-time high 19.72 per cent in November as food prices spiraled.

It was the same year that the shilling was battered to become one of the worst performing on the globe that time. At Sh 106.75 against the US dollar in October, the import bill became huge, foreign reserves were overstretched and it felt like the economy was grinding to a halt.

But when global oil prices eased, Kenyan economy, with more than a quarter of its import bill coming from oil, got the headroom to breathe. The shilling started gaining against the US dollar opening 2012 at an average of 87 to the dollar. To the exporters, this meant more money in their pockets.

Compared to 2014 when a barrel of oil was $97 (Sh 9,834), it almost halved to an average of $45 (Sh 4,562) in 2015. Before the drop in prices, oil used to account for over a quarter of the country’s import bill.

Renaissance Capital, an investment and research bank that focuses on emerging markets like Kenya, had warned that the narrowing deficit that followed was unsustainable especially if oil prices recover.

“The shrinking of the import bill masks the under-performance of Kenya’s export sector. Since 2011, when exports to GDP came in at 13.7 per cent, it has fallen 9.6 per cent in 2015,” it said.

Current account deficit (A measurement of a country’s trade where the value of the goods and services it imports exceeds the value of the goods and services it exports) had improved to a five-year low of 5.4 per cent of GDP in the third quarter of 2015.

This was from about nine per cent in mid-year even as foreign exchange reserves accumulated to a high of five months of import cover in the second quarter of 2016.

Procurement system

Usually because of 30 to 45 days’ time lag between procurement and delivery, Ng’ang’a said that he expects the impact to be felt in the next two or three months. The latest impact, Ng’ang’a said in a phone interview, will not be captured in the mid-December to mid-January pricing. Instead, consignments shipped in between November 9 and December 10 are the only ones that will be will be considered..

Powell Maimba, the chairman of Petroleum Institute of East Africa said that he expects prices to rise because the OPEC decision has been made at a time oil was already showing signs of recovery.

“I expect the cost of living to also start going up in February or March as the prices start getting reviewed upwards,” he said, adding that oil will put pressure on import bill. Already, inflation is at a nine-month high at 6.68 per cent in November after a sustained rise in three consecutive months.

However, Maimba said that the OPEC deal may not see the prices rise beyond $60 per barrel since the oil that had been produced is already too much to clear. To him OPEC may just be creating artificial impact to make some revenues then backtrack on the deal.

Already, analysts are warning that the shilling could run into the headwinds of elections, the likelihood of US Federal Reserve rising interest rate and US President-elect Donald Trump favouring protectionist tactics.

According to Jeff Gable, the Barclays Africa Head of Research and Chief Economist, the shilling may drop to a 15-year low in the next 12 months. “We expect a continuous depression into 2017 with the biggest role related to election and a strong US dollar. The headline number is past Sh106,” Gable said.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.