×

The Standard e-Paper

Fearless, Trusted News

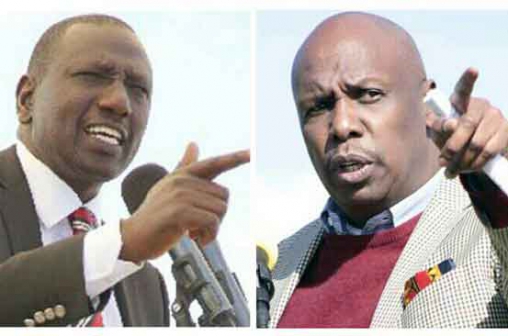

Deputy President William Samoei Ruto has been criss-crossing the Great Rift Valley collecting debts, political debts. His greatest debtor, it seems, is Baringo Senator Gideon Moi.

According to Ruto, the senator should pay his political debts urgently because "we (Kalenjins) supported his father's presidency for many years".