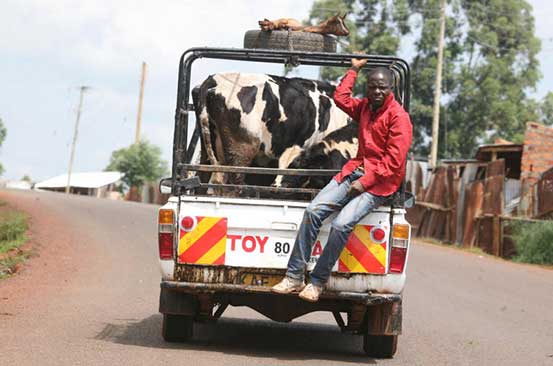

Transferring animals from one region to another is fraught with risks. Many farmers fear that an animal will not survive if moved to a region different from the one it originated from. It is true that many animals have died or under performed on arrival in new areas. But this need not happen if farmers implement certain measures to prevent this.

An animal has to deal with the stress of travelling. When it arrives at the new region, it has to deal with such issues as too much heat or too much cold, a change in the type, quality or quantity of its diet, new bacteria, viral, protozoal or fungal infections and parasites such as worms.