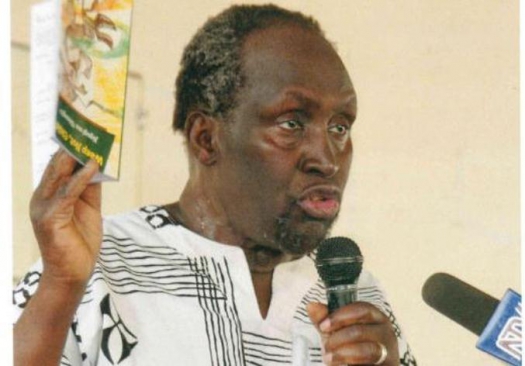

Someone once said there could never be too much of a good thing. Prof Ngugi wa Thiong’o has travelled back to the US, yet he said much about writing while he was around for the last two weeks, that could be a good lesson for young writers.

When he was asked the secret to becoming a great writer he said, “Write, write and write again, then you will get it right.” What Ngugi meant was that practice makes perfect. The more you write the more you learn and the better you become. You also draw from your experiences to develop great stories.