×

The Standard e-Paper

Smart Minds Choose Us

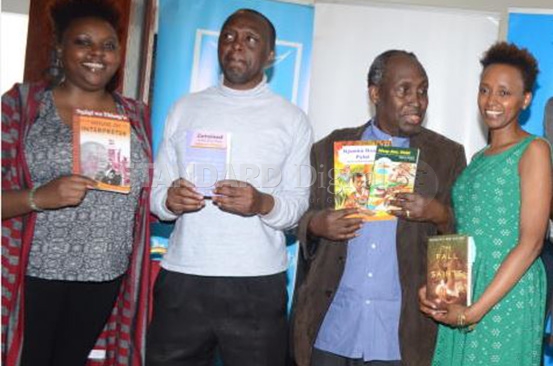

Renowned author Ngugi wa Thiong’o, 77, returned to Alliance High School this week with a bright red shuka draped over his shoulder – having been freshly enthroned as an elder – clutching a memoir documenting his time there.

Animated, energised and occasionally, downright humorous, the distinguished academic, provided anecdotes from his student life at the colonial school nearly 60 years ago, providing insights that deepen and extend our understanding of the ideological underpinnings of his writing.