I once took an online health journalism course whose one module was a shocker; it was simply titled “Think”.

It had nothing to do with health, but everything to do with just about anything in life. Using simple practical exercises, the course showed how we go through our daily routines like robots without much thought, most times following the crowd.

The result is disastrous. It leads to failure to internalise issues leading to lack of originality. In education, we cram for exams, or use a mwakenya (a cheat sheet).

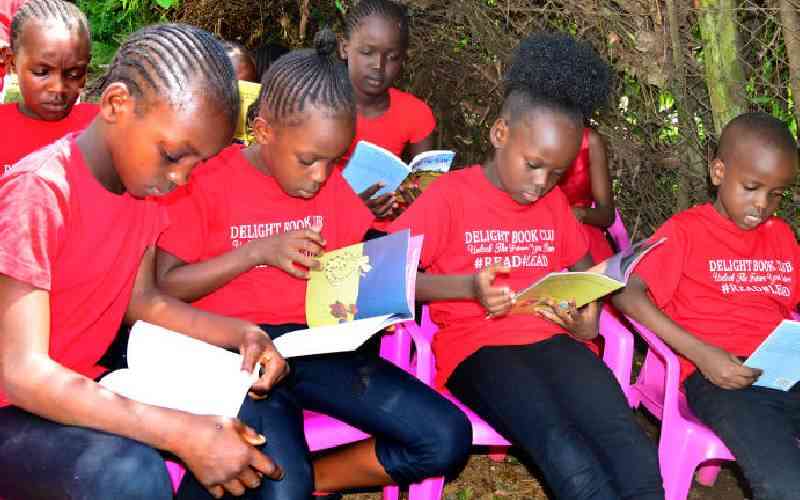

Meditation and reading, showed the course, are sure-fire ways of sharpening thinking skills, as Fran Lebowitz, the American author and essayist says, “Think before you speak. Read before you think.”

The question is what to read from the truckloads of books out there in all form of genres. Muthoni Garland of the popular literally Storymoja Festival will tell you fiction fires imagination. Others will quote motivational writers, or writers who lean towards spiritualism and reflection like Paulo Coelho and Robin Sharma.

Hand grenade

Luckily for us, we no longer worry too much about what to pick from the shelves for finally from Kenya comes an author whose writings not only provoke thought, but arouse the age-old questions of identity and mortality.

Renowned essayist Waithaka Waihenya has compiled his popular pieces that appeared in The Standard in the mid-1990s as The Sunday Essay in a book.

The Sunday Essay gained a huge following and having folded in 2007, ardent newspaper readers remember it nostalgically.

“The Sunday Essay spoke to my soul,” says The Standard arts and culture writer Mbugua Ngunjiri as he fingers Waihenya’s new book, Dancing in the Twilight: Essays on Mortality, Love and Self.

Indeed. In the preface of the book, Waihenya, a veteran journalist and the Managing Director of the Kenya Broadcasting Corporation echoes Ngunjiri:“...the best form of writing is the one that talked to the soul, the one that allowed the writer to travel long distances in the mind, churning and turning over the humus of thought consistently so as to affect some form of dialogue with the psyche.”

And Waihenya provokes intra-personal dialogue in this book as he delves into intricate matters of love, religion and even death with a literally touch, like when he terms suicide as a plot against one’s life.

“If a hand grenade was a living thing,” writes the man who started confronting the question of suicide after his 34-year old friend plotted against his own life, “it would very much resemble a suicide’s mind. For a suicide has a grenade quality,” he writes, adding, “he carries his own doom in his own enclave, holding the safety pin in the palms of his fateful hands... waiting for the moment when the ‘pop’ sound would go off and all disintegrates in a dusty wastefulness, futility and death.”

But the book also has hearty moments, like when Waihenya gets lost in San Francisco. Efforts trying to ask for directions are met with suspicions and curt dismissals. He sees men queuing as if to get into a movie theatre and with nothing else to do, joins them. But to his horror, when he approaches the end of the line, he realises the line heads into a brothel. He scampers away.

But in his deep introspective way alive in the 272 pages of the book published by One Planet, Waihenya learns from the experience, and only stops short from dismissing San Francisco as ‘such a Godless City.”

Stay informed. Subscribe to our newsletter

Read meat

Contemplatively, he wonders whether he turned away because he is good and not a sinner and at the same time acknowledging, rather controversially to the pious, that “some (people) sin because they are courageous; others shun sin not because they are good but because they lack the courage to sin.”

The book, divided into eight parts moves in the same vein with short, punchy essays, and in part two, Self, Spiritual and the Matters Soul, we meet pieces which take us back to Think, and into the author’s mind.

In Splendours of Silence, Waihenya visits a stark truth. That we are a society inundated with noise, and charges that it is only in solitude that we can connect with the soul ‘with a seductive charm’, recall the past and glance into the future with a ‘prophetic sight.”

In essence, solitude and meditation is good for the soul and creativity. However, as he notes in the essay, Bosom of my Saturdays, we would rather be gulping mouthfuls of alcohol and red meat at the local, than taking long walks in the woods.

In this book, Waihenya has bequeathed his loyal readers a jewel, because, unfortunately in our dailies today there is a dearth of such writings, as are authors of the essay genre.

A worrying state of affairs that Frederick Iraki, a Professor of French at the United States International University, Nairobi, notes in the book’s forward could be due to our higher learning institutions failure to produce thinking and reflective people.

The Professor says thinking, as the Think course mentioned above showed, is a hard job, sounding a death knell into our future, even as the world basks in the creative knowledge economy, which is driven by thought.

That is why Waihenya suggests the essay be introduced in the school syllabus.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.