My bodyguard since I first entered Parliament seven years ago is a fine police officer called Jonah Rotich, a pure bred Nandi gentleman from Uasin Gishu County. My Personal Assistant is a young lady of Gusii extraction from Nyamira County, MarieClara Mayaka. I’m always amused by the eyebrows raised virtually instinctively whenever it is revealed that I have “strangers” working with me so up close! It reminds me constantly just how powerfully the genie of tribalism has enslaved our conscience.

The damn brutal truth is that we, Kenyans, are hopelessly tribal, innately so. In our thoughts. In our talk. In our actions. Our outlook is heavily nuanced by tribal blinkers. We whine how tribal so and so is. Yet that is the one characteristic that influences many of us the most.

We complain about how employers overlook merit and prefer tribal affinity. Yet we expect “our own” to naturally favour us when in positions of authority. We rant how this or that president loaded government with his kin. Yet, the primary motivation for supporting our tribal dons is the expectation that they will indulge us when in power. We are such a web of contradictions!

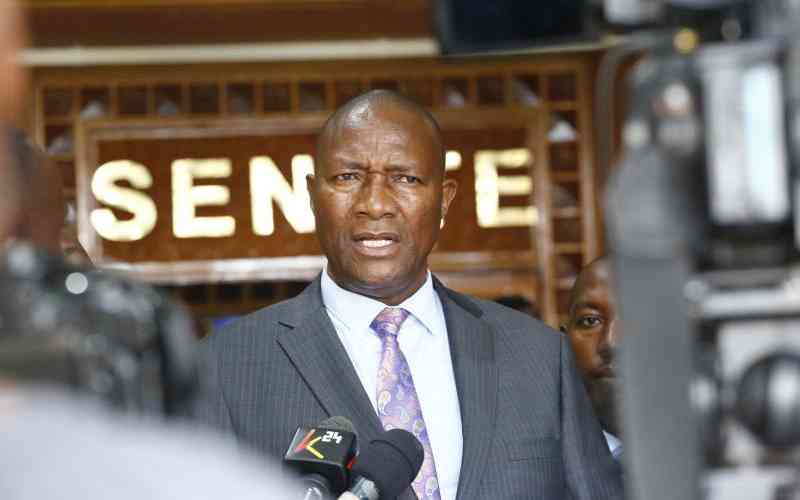

Our tribal instinct actually is the stuff of paranoia and xenophobia. It feeds our most base fears, and nourishes the overpowering sense of ethnic mistrust and contempt that poison our relations. Ours has been reduced to a society defined by an acute trust deficit. Persons elected to serve the nation find it difficult to trust anyone out of their tribal kinship. When selecting the aide-de-camp or chauffer for the President, the primary consideration is likely to be ethnic complexion. When a Member of Parliament picks his bodyguard, he will care more about the surname than ability. Who would trust a “stranger” with their security? Our last names do betray us, indeed!

The result is that this tribal orientation defines virtually all our national endeavours. It has turned our politics into a messy ethnic warfare, with tribe the focal point for political mobilisation, instead of distinctive ideological platforms. Inciting tribal emotions is accordingly more premium than appealing to any sense of objectivity. Everyone, media included, measures your political worth in terms of your “ethnic capital”. To play on the national stage, you must first strive to be a tribal kingpin.

Once elected, you become a virtual slave of your tribal “keepers of the throne.” Tribe has also completely distorted key national agenda like the war on corruption. Common thieves routinely rob the public, but when caught, they run to the tribe screaming “we are being targeted, they want to finish us,” cleverly turning individual culpability into communal liability. Employment is similarly soiled, as merit is habitually sacrificed at the altar of ethnic jingoism.

Our ethnic diversity is potentially a major asset. But unlike our neighbour Tanzania that has succeeded to morph her numerous tribes into one cohesive unit with primary allegiance to the nation, we have turned ours into a curse. We pay lip service against it, yet practice it with aplomb. The resultant venom is a perpetual national tragedy that robs the country of the colossal benefits of synergy, merit, fairness and positive energy. To paraphrase Martin Luther King, we judge each other by the letters of their surname instead of the content of their character.

If they pander to our ethnic prejudice, we celebrate them. If they don’t, we condemn them. When Raila Odinga declares “Kibaki Tosha”, he is “Njamba”, a venerable warrior to the Kikuyu. The moment he falls out with Kibaki, he becomes public enemy number one in the mountain region! William Ruto supporting Raila Odinga is a hero to the Luo nation. When he breaks away from Jakom, he is unacceptable to Kavirondo. Could a society get more ridiculous, really!

We ruined the plot soon after independence, and lost a glorious opportunity with the wasted “Yote Yawezekana NARC moment.” Even our long sought new constitutional order stands at a crossroads, with plastic measures like the NCIC achieving very little. Because the problem lies in our hearts and minds. For, as noted by Gandhi, “a man is but the product of his thoughts. What he thinks, he becomes.”

Because no problem can be solved from the same consciousness that created it, each one of us must make a conscious decision to be the change we want to see in Kenya. And since we will never wish each other away, anyway, why not just accept King’s ageless wisdom: we must live together as brothers or perish together as fools!

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.