|

|

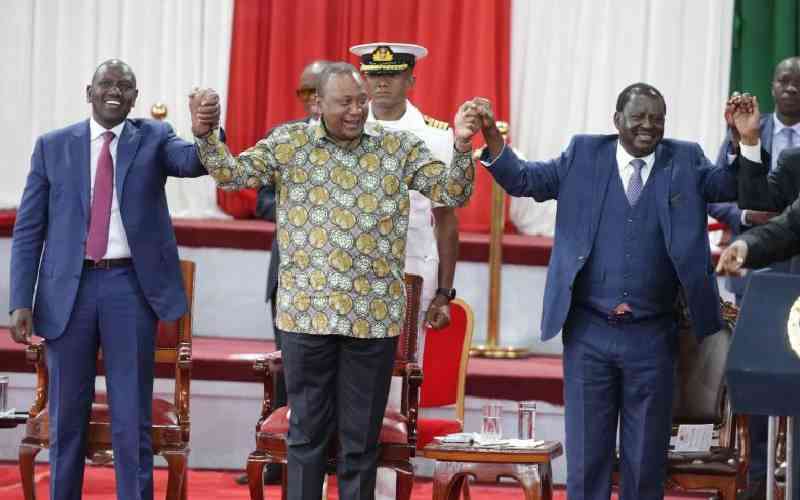

Prosecutor Fatou Bensouda wants Kenyan authorities to hand her President Kenyatta’s financial records. [PHOTO: FILE/STANDARD] |

By FELIX OLICK

[email protected]

NAIROBI, KENYA: As the International Criminal Court (ICC) faces increasing challenges in pursuing prosecutions, there are few signs that global powers will step up and give the institution the political backing it needs.

Since beginning its work in 2002, the ICC has struggled to apprehend high-profile fugitives like Sudanese president Omar al-Bashir, who is charged with genocide in Darfur.

In two ongoing cases in Kenya, the court has found it hard to secure cooperation from the government as it seeks to prosecute President Uhuru Kenyatta and his deputy William Ruto.

In the Sudan case, judges in The Hague recently called on the United Nations Security Council to take action against the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) because the authorities there failed to arrest Bashir while he was in that country.

In their April 9 decision, judges warned that efforts to deliver justice would be in vain if the ICC did not get the necessary backing from the Security Council, the body that referred the Darfur conflict to the court in 2005.

“If there is no follow-up action on the part of the Security Council, any referral by the Council to the ICC… would never achieve its ultimate goal, namely, to put an end to impunity,” judges warned in a written decision. “Accordingly, any such referral would become futile.”

Shortly before issuing this decision, the ICC also threatened to refer Kenya to the court’s 122 signatory states – known collectively as the Assembly of State Parties (ASP) – if the government failed to cooperate. However, it is unclear what states could actually do in this eventuality, since the ICC’s Rome Statute does not outline particular actions and the ASP cannot impose sanctions.

Prosecutor Fatou Bensouda wants the Kenyan authorities to hand her Kenyatta’s financial records which she hopes will support charges that he bankrolled ethnic violence six years ago.

Kenyatta and Ruto are charged in two separate ICC cases with orchestrating the two months of bloodshed that followed Kenya’s polls in December 2007. A third defendant, Joshua Arap Sang, is on trial in the same case as Ruto.

In a decision issued on March 31, judges delayed the start of Kenyatta’s trial until October 7 in order to give the Kenyan authorities a further opportunity to hand over evidence.

International justice experts have told the Standard on Sunday that the UN Security Council and the ASP may be of limited help to the court as it seeks to push ahead with trials.

“I'm not sure what the ASP can do, other than issue statements and try to make sure its individual member states take action to encourage Kenya to cooperate with the court,” said Mark Kersten, a doctoral researcher at the London School of Economics. “It would certainly be an unprecedented development if the ASP homed in on one specific state and attempted to force its members to act.”

The way the Kenyatta and Ruto/Sang cases have unfolded over the last year has made experts particularly sceptical that the ICC or its member states would want to make an example of Kenya. The court’s relationship with the country, as well as with the wider African Union (AU), has become increasingly strained since Kenyatta and Ruto came to power following last year’s presidential election.

Stay informed. Subscribe to our newsletter

Both Nairobi and the AU – which includes 34 ICC member states – have asked the court and the Security Council to terminate the two Kenya cases. They also made an unsuccessful request to the Security Council to delay the cases by a year.

Last September, Kenya’s bicameral parliament voted to withdraw from the court altogether, and the idea of other AU states following suit was floated at a subsequent summit in Addis Ababa.

Anthony Dworkin, senior policy fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations, said that such tensions would make the ASP reluctant to act against Kenya.

“I think the ASP will proceed very cautiously on this question, because of the sensitivity of the court’s relations with African countries,” he said.

Up to now, resistance within Kenya and on the African continent to putting incumbent state officials on trial has been met with sympathy from the ASP. During its annual meeting in The Hague in November, the ASP scheduled a debate, at the AU’s request, on the problems associated with prosecuting a sitting head of states.

The move followed calls from the AU to change the Rome Statute to grant heads of state immunity from prosecution as long as they were in office. Kenya has since tabled a formal proposal to this effect.

In what some saw as another effect of Kenyan and AU pressure, Britain and other European states then proposed an amendment to the court’s rules which enables judges to allow senior public officials to be absent from trial in The Hague. The rule was subsequently changed with unanimous agreement, highlighting the kind of concessions that states are prepared to make over ICC cases.

“Kenya has goodwill from the ASP as a whole,” Muthoni Wanyeki, regional director for Amnesty International in Nairobi, pointed out.

In the context of efforts to placate Kenya and keep the AU on side, neither the court nor powerful supporting states like Britain would want to risk escalating things.

“No party or state has an interest in the ICC-Kenya matter blowing up in a major diplomatic or political row,” Kersten said.

As well as taking local resistance to the ICC into account, Western states will also be considering their own wider interests in Kenya and the East Africa region. Many, Britain and the United States among them, have long-term security and economic interests which they are reluctant to jeopardise for the sake of the ICC.

Kenyan troops are currently waging a battle against al-Shabaab militants in Somalia. Senior Kenyan figures believe their country’s importance in the fight against terrorism, coupled with economic interests, mean that no Western state is likely to take strong action.

“Due to the country’s geopolitical importance, the West will have no option,” Ambassador Ochieng Adala, Kenya’s permanent representative at the United Nations in 1992-93, told the Standard On Sunday. “Their interests will trump any other consideration.”

Prior to the March 2013 presidential ballot, Western governments indicated that they would be unhappy if Kenyatta and Ruto were elected, given the ICC charges. The US warned of “consequences” if they won, while Britain said that it would only have “essential contacts” with them as long as they faced trial in The Hague.

That view has changed. This August, Kenyatta will visit US president Barack Obama in Washington, and he has already been welcomed in European countries.

Makau Mutua, chairman of the Kenya Human Rights Commission, has hit out at the international community for giving the impression it is no longer interested in Kenyatta going to trial.

In an op-ed article on the Standard newspaper on April 27, Mutau described a recent photograph of envoys from the US, Britain, Canada and Australia in which they were “bowing - some might say even supplicating — to President Kenyatta”.

“It’s my submission that the West has already blinked – thrown in the towel,” Mutua wrote.

Other commentators agree that harsh measures such as sanctions are unlikely, but point out that a simple referral to the ASP might still have negative repercussions for Kenya.

Luke Moffett, a law lecturer at Queen’s University in Belfast, said he would expect the ASP to respond to any future referral by issuing a statement calling on Kenya to cooperate with the ICC. He said the ASP might also ask civil society groups to increase pressure on the authorities, arguing that such steps could affect diplomacy, trade and tourism in Kenya.

“The ASP is perhaps toothless, but not entirely useless,” he observed. “It may not be able to bite a state through sanctions, but its bark of highlighting the non-cooperation of a state party can bring international condemnation, public outcry, and media attention.”

In a separate effort to put political pressure on states to support its cases, ICC judges recently referred the DRC to the ASP and the Security Council for not arresting Bashir when the Sudanese leader visited in February for a summit of the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa.

But despite this warning from the ICC, experts again doubt that the UN Security Council will take action.

The decision to refer DRC follows previous referrals by ICC judges after Bashir visited other ASP states including Kenya and Chad. None took steps to arrest Bashir, as they were required to do.

Danya Chaikel of the International Association of Prosecutors says that given its track record, “it is unlikely that the Security Council will react boldly to the ICC’s referral”.

“Most likely it will do nothing at all,” Chaikel noted.

According to Chaikel, arresting Bashir raises complicated legal issues, and this may be behind the Security Council’s inaction. Some states have argued that they do not have a legal obligation to arrest Bashir because Sudan is not a party to the ICC treaty and therefore has immunity from prosecution as a head of state.

“This might be contributing to the UNSC's inaction,” Chaikel said.

Others point to different factors that the Security Council might be considering.

Moffet argues that there are legitimate concerns about the risk of destabilising Sudan, particularly given the ongoing tensions with its southern neighbour, South Sudan, and the internal conflict taking place there.

He also points out that the UN Security Council has to consider the current security problems along the Sudan-DRC border, where rebel groups like the Lord's Resistance Army continue to commit atrocities.

“Thus, while there are clear obligations which states should follow under the Rome Statue, in practice there are other prevailing factors which suggest non-cooperation is better [in order] to maintain relations with other states or national security,” Moffet said.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.