×

The Standard e-Paper

Home To Bold Columnists

|

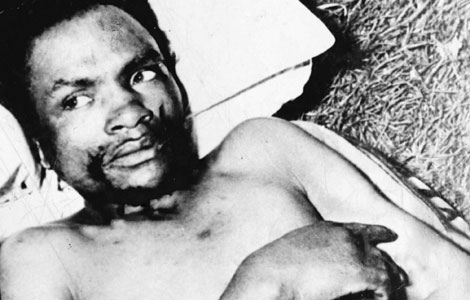

| Freedom fighter Dedan Kimathi. (Photo:File/Standard) |

By Kiundu Waweru

Kenya: Mau Mau fighter Dedan Kimathi was born of the Ambui clan, one of the nine clans of the Agikuyu tribe.