By Barrack Muluka

What you see of the conduct of any society is a statement on the education the people have had. Education in itself must mean more than getting grade ‘A’ in Chemistry and Geography.

It is indeed the totality of the knowledge, skills, attitudes, beliefs and behaviour that we pick up and internalise as we prepare to deal with our environment.

A people can never be better or worse than what their education has prepared them to be.

When we see killer madness on our roads, such is what our education has prepared us to do. If we have made our environment the filthiest in the universe, our education prepared us to do exactly that. If we are thieves, or whatever else we may be, put it to our education.

And this is education that we acquire right from the cradle, at home. Our first school is at home. We learn from our parents and model ourselves after them, consciously or otherwise. Some other things we learn from our playmates and friends.

Others from those older than we are. They are our role models and stars. We aspire to be like them, when we grow up.

But then we have the school.

This is the place meant to level our learning and prune our wild instincts and weed out bad training from elsewhere. Eventually, we should leave this place not just ––having attained grade ‘A’ in all subjects, but also having learnt to live in society in socially acceptable fashion.

That is why they say we are civilised. When they say this they do not mean that we have good houses and cars, or that we travel by air and eat in five star hotels. To be civilised simply means to be able to live in peace and harmony with other people, being conscious of their rights and welfare.

How civilised are we then, we people called Kenyans?

Consider the normal things that we do everyday. This week I saw a university professor, whom I know by name and face, passing warm water on the roadside, next to his pick up van.

He seemed quite comfortable with this exercise, along James Gichuru Road, in Nairobi’s suburbia.

Elsewhere at the urinal, some characters were running their mouths like mad, splashing the wall with warm water. They walked away merrily, without bothering to wash their hands. I caught one of them shaking hands with other people, soon after. And of course I said to myself, “Hun! The hands we shake!”

Then there was the character who was going on and on at the top of his voice on his phone at the bank at Yaya Centre, once again in upmarket Nairobi. He was offering his car to someone in lieu of money he owes the other character. I left him still screaming the negotiation on the phone, in total disregard of the postings on the wall, cautioning against talking on the phone in the bank hall. But this is who we are.

Stay informed. Subscribe to our newsletter

The school is expected to moderate the things that we have learnt from other environments and teachers. In a gone age, you told the schooled lady or gentleman from very small things.

They were things that would not seem to matter to other people. But those were the unschooled people – the uncouth.

The sort of fellow who presses his nostril shut with one finger and blows out mucus through the other nostril.

He coughs into your face, or across the dining table. He rinses his hands by shaking off the water and wipes the rest on his cloths, or in the pocket. He talks with his mouth full of food. He has never heard of such simple expressions as, “Excuse me. May I? Could you kindly? Thank you.”

But have we as a nation not become this unschooled character?

A certain hyenaism has gripped us to the extent that we have lost the capacity to feel ashamed. Being schooled means having the sensibility to be ashamed of some things. The ability to be embarrassed and to keep asking yourself, “How could I have done that?”

This is regardless that other people get to know of what you did or not. But may be it does not matter. May be you are the kind of person who says, “Who cares?” In which case you are dead. You are a walking corpse – a zombie.

This explains why Engineer Michael Kamau’s good intentions to restore sanity on Kenya’s roads by making all of us take fresh driving tests will not work.

We are dead, inside. Deep down, there is no human soul in us.

For education hones the human soul and the superego, placing them in charge of our judgements and activities.

If our natural thrust is towards pushing other motorists into the ditch because we do not respect their right of way, retaking the driving test will not change us. A few minutes after the test, we will do the selfsame things we have always done.

Over the years, the African nation has degenerated into one huge mental hospital. The difference between this hospital and the rest is that there are no doctors.

That is why even Europeans and visitors from elsewhere soon catch the disease on Kenya’s roads. What we need is, therefore, not taking fresh driving tests.

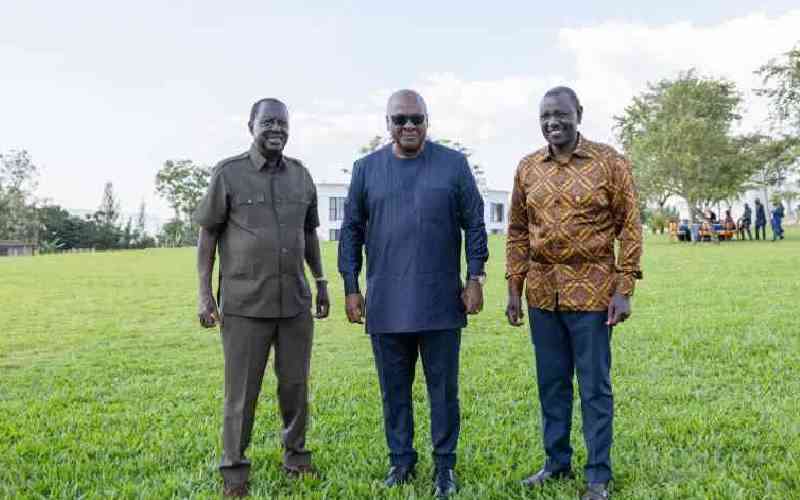

What we need is a ruthless therapist in the image of someone like President Paul Kagame of Rwanda. We need someone who can cause us to be removed from our cars to be canned on the spot for breaking traffic regulations, or for littering and a cocktail of other social maladies.

President Kenyatta may wish to borrow some of these methods from his friend in Kigali.

The writer is a publishing editor, special consultant and advisor on public relations and media relations

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.