By EMMANUEL WERE

Picture this: A blue chip company appoints a new chief executive to lead its turnaround strategy. The company has been struggling because it has not fully exploited its resources — maybe patents and human resource — unlike its competitors.

Naturally, the CEO will be in the limelight. Can he or she successfully lead a turnaround strategy? What is his or her track record?

As devolution begins to take shape, Business Beat is looking at the counties in a different light. Counties become companies and governors their CEOs.

We have started with a look at five counties — Nairobi, Machakos, Kitui, Kwale and Turkana — through the prism of their governors.

What is their business acumen? How have they exploited opportunities in the past? In understanding the past of most of the governors, we believe investors and residents would be in a better position to understand the future.

Of course, there was a long debate about which counties to pick. In the end, we settled on these five because, apart from Nairobi, they are in the bottom half of the wealthiest counties, according to a ranking by the Commission on Revenue Allocation released mid this year.

Why these counties?

These four counties have newfound resources that could turn their fortunes around if well utilised.

Turkana has its interesting mixture of oil and water. Kwale has its mineral deposits of rare earths. Kitui has its coal and limestone, which has attracted the interest of Africa’s richest man, Aliko Dangote. And then there is Machakos. Well, what does Machakos have? In our opinion, we think the county is positioning itself as an information hub. If the Konza City concept takes off, Machakos will be home to several global companies and Kenya’s very own blue chips.

The information technology players, some say, will be the biggest beneficiary of Konza City, but a close analysis says the trickle down effect, if well managed, will be huge.

Nairobi finds itself on the list because it contributes nearly half of Kenya’s GDP.

Turkana

When the first mobile phone network signal reached Turkana County in 2005, JOSPHAT NANOK saw an economic and political opportunity that was not that obvious to many.

Nanok, 43, was then campaigning for the Turkana South parliamentary seat in the 2007 General Election.

Stay informed. Subscribe to our newsletter

He bought hundreds of Nokia mobile phone handsets and distributed them to homesteads in Turkana. In an area prone to cattle rustling and insecurity, the phones came in handy for the pastoralist community, and he acquired a new nickname for his efforts — Nokia. He went on to become the Turkana South MP.

Five years later, “Nokia” had even bigger ambitions — the governorship. After the Baragoi massacre that left more than 40 police officers dead, Nanok was among political leaders arrested on claims of incitement. His case was dismissed for lack of evidence. And in true style, he found a way to make lemonade from lemons.

When the government sent military troops to the region to conduct a rigorous disarmament exercise, most residents fled their homes, fearing the operation would turn violent. Nanok was among Turkana leaders who petitioned the government to call off the operation, which worked as the disarmament was made voluntary.

Nanok took responsibility for the change of heart. The electorate nicknamed him “Abuwang’imoe”, meaning “he who repulsed the enemy”, and he became Turkana’s first governor.

The Commission on Revenue Allocation ranks Turkana the poorest county in the country. However, it is the second-largest in terms of surface area, which is turning out to be quite a useful resource both below and above ground.

First was the development of Africa’s largest wind power plant, then the discovery of oil and now the discovery of aquifers containing 250 billion cubic metres of water that experts say can serve the country for 70 years. This makes Nanok one of the most powerful governors in the country, charged with managing vast resources.

Given his nose for making the best of opportunities, it is a safe bet Nanok will find a way to get the most out of his county’s natural resources.

He describes himself as “persuasive, diplomatic, an accomplished strategist and negotiator”, and holds a bachelor’s degree in political science and history from the University of Nairobi. Nanok spent most of his professional life in international development organisations.

Nairobi

It has been a rocky start for DR EVANS KIDERO, who has moved from one crisis to another — both personally and politically.

The chief executive of Nairobi, which generates more than 45 per cent of the country’s GDP and is ranked the sixth-richest county, is in a quandary. The county needs Sh6 billion, but there are so many revenue leaks that if he turns to investors to raise the money, it will likely be gobbled up.

Kidero was born in Majengo, in the Eastlands area of Nairobi. His father was a policeman, his mother a homemaker. He is the eldest of seven children.

He was headboy at Mang’u High School, and studied pharmacy at the University of Nairobi. His first job was as a pharmacist at the Kenyatta National Hospital. He got an MBA in 1990 at the United States International University in Kenya.

These qualifications, and his personal abilities and triumphs, set him on the path for an illustrious career in corporate management. It is this experience that will be tested as he steers Kenya’s capital city.

Kidero spent four years at Warner Lambert, 12 years at SmithKline Beecham Healthcare International, two years at the helm of Nation Media Group and most recently, 10 years as Mumias Sugar Company CEO.

Kidero’s personal experience overcoming the challenges of growing up in Nairobi with minimal resources and his vast business experience make him an ideal chief executive for Nairobi County. But the task ahead of him will require as much brawn as brain.

A report by audit firm PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC) two years ago revealed that a third of City Hall’s 11,000 workers were dead, non-existent or used forged papers to get a job.

Kidero will have to leap various hurdles to recruit the right kind of staff, put in place a workflow plan and work out an appropriate remuneration package.

Nairobi County is also heavily indebted. When Kidero took office, City Hall owed various creditors in excess of Sh5 billion.

He must also find fast and lasting solutions to the perennial problems of uncollected garbage, water shortages, inadequate or poor sewerage and sanitation, corruption within licensing departments, and insecurity within the city.

Kidero has, however, been so busy sifting through the mess at City Hall that his strategic vision for the county has yet to be adequately communicated to residents and potential investors.

Kwale

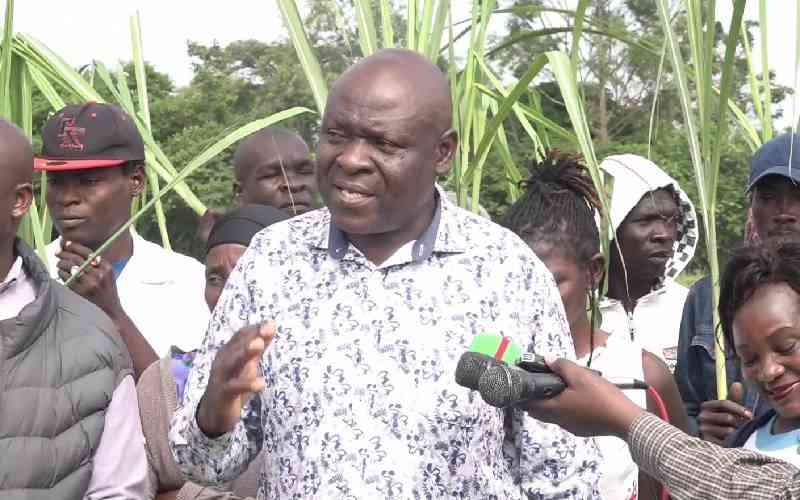

Kwale Governor SALIM MVURYA manages several natural resources that could propel growth in a county ranked the seventh poorest in Kenya. Kwale sits on minerals such as niobium, titanium and rare earths estimated to be worth trillions of shillings.

Sugarcane is another resource that has escaped many looking at the county. Kwale International Sugar Company (Kiscol) recently raised Sh10.5 billion from a consortium of banks to finalise the construction of a distillery, milling and power plant. The project will be completed by June 2014. Omnicane, a sugar miller listed on the Mauritian stock exchange, has a 25 per cent stake in Kiscol, bringing on board much-needed expertise to run the project.

Minerals are a major source of conflict as international players and local tycoons eye wealth from the trade of these minerals. Sugar is also a very politicised commodity in Kenya. Because the country produces less than it consumes, there is always an opportunity for unscrupulous traders to import very cheap sugar and sell it in the local market.

Mvurya’s true test will be balancing the many interests surrounding the exploitation of these resources. But those who know him say he is more of a fence sitter and avoids confrontation.

“He tries to avoid anything that is controversial,” said a person close to him. “People have started complaining because when they go see him, they instead end up meeting with Deputy Governor Fatuma Achani.”

Mvurya’s shying away from “dirty politics” might have to do with his professional background. This is his first time in politics; he left the NGO Plan International to run for the governor seat in the March elections. Mvurya laid the ground for his entry into politics while at Plan, coming up with a number of school and farming projects for the community. This endeared him to the locals.

Although, he campaigned with grand visions for Kwale County, his six-month tenure has not been smooth sailing. There have been cases of land grabbing, with an audit yet to be done. And in August, Mining Cabinet Secretary Najib Balala suspended more than 30 mining licences, saying the correct award procedures were not followed. The biggest casualty was Cortec, which discovered niobium and rare earth minerals in Kwale estimated at Sh8 trillion.

Kitui

DR JULIUS MALOMBE should in the near future play host to Aliko Dangote, Africa’s richest man, who plans to put up a Sh35 billion cement factory in Kitui. The factory will be powered using the county’s coal reserves.

It will be a win-win situation for both men.

Malombe will be set up as a key power broker in the country, while for Dangote, it will mark an important step in his quest to be the largest cement producer in the world.

Those close to Malombe say fully utilising coal reserves to spur economic take off in the county is his top priority.

Kitui sits on about 500 million tonnes of coal valued at Sh3.4 trillion — about the value of Kenya’s GDP last year. Limestone is the county’s other resource.

But for Malombe, who is in his first stint in active politics, it will be a delicate balance attracting investors to the county and lifting its residents out of poverty. His campaign was built on plenty of chutzpah and the promise to better agricultural production and increase access to water for the people in Kitui.

He has worked as a private consultant in urban development and finance.

The skills gained from these two sectors will be important in reversing the fortunes of a country ranked 35th in the poverty index, despite it having arguably one of the largest mineral resources.

Malombe, the former chairman of a taskforce on devolved government, says his clarion call “Utongoi waw’o tutonya kuikiia na kuwitikila” (Time for leadership we can trust and believe in) is what people in Kitui need to move forward.

The governor, who is known for having a calm demeanour, expresses his vision as: “I stand for an inclusive, well-managed, people-centred and service-oriented county government. A county government that uses its human, natural, financial and other resources sustainably and in a transparent and accountable manner.”

Malombe said for the county to grow, its resources need to be well harnessed, and promised to offer a brand of leadership that would be synonymous with integrity.

Malombe has called on his county executive committee to serve devotedly for Kitui to realise its potential.

Machakos

When Kenyan filmmakers were decrying the lack of corporate sponsorship that would give them the financial muscle to produce local content, DR ALFRED MUTUA did not join them. Instead, he localised a concept known in the West’s entertainment industry as payola.

Under a payola agreement, instead of selling content directly to media houses, film producers buy space to air their programme. The upside is that the producer benefits directly from any advertisements brought in.

In what would turn out to be a very shrewd move, Mutua secured advertisers for his production, Cobra Squad, bought a TV slot to air it and got to keep all the advertising revenue.Reports have it that he made so much money that he was able to finance the construction of his home in just one year.

The former Government Spokesman has successfully used his public relations skills to sell his vision of Machakos to investors, despite the county not having any major natural resources. Mutua has met with investors, held seminars on business opportunities and organised roadshows to market Machakos as an investor’s dream.

The county, which is ranked the 17th poorest, has the fifth-largest share of Kenya’s urban population, which is an attractive market for potential investors. It also has Konza City, the Promised Land for the Kenyan IT fraternity, which is looking to create a “Silicon Savannah” styled after northern California’s high-tech Silicon Valley.

Mutua is described as a go-getter who dreams big. His book, How to Get Rich in Africa and Other Secrets of Survival, is testament to that. His likely approach to turn his dreams for Machakos into reality is best understood by looking at some of the brazen moves he has made in the media industry.

Early in his professional career, after going weeks without pay as a correspondent at a local daily, Mutua stormed into the finance manager’s office to demand his dues. The move was so unexpected that he was immediately paid from the petty cash fund.

But the questions about him are whether he will stay on the path he has set. Some of his projects have ended up falling by the wayside, most recently society magazine Passion.

He is also known to stick by his opinion, even when he is wrong. Investors must hope Mutua has got it right about Machakos’ potential.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.