×

The Standard e-Paper

Smart Minds Choose Us

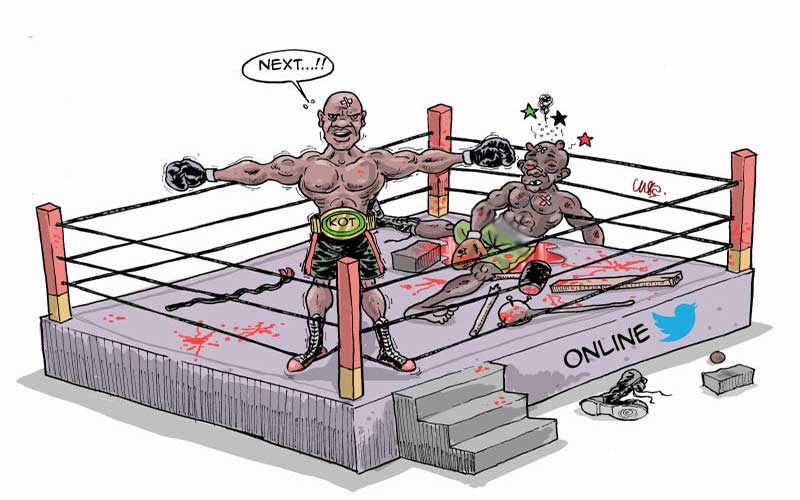

The recent incident that saw two groups of youth clash in Murang’a paints a clear picture of the reality that is political expression in Kenya. It represents a physical equivalent of what happens online between self-avowed political bloggers in support of different political camps. As the youth in Murang’a exchanged physical blows and burnt tyres, their counterparts took to their keyboards to continue the ‘war’, albeit virtually.