×

The Standard e-Paper

Home To Bold Columnists

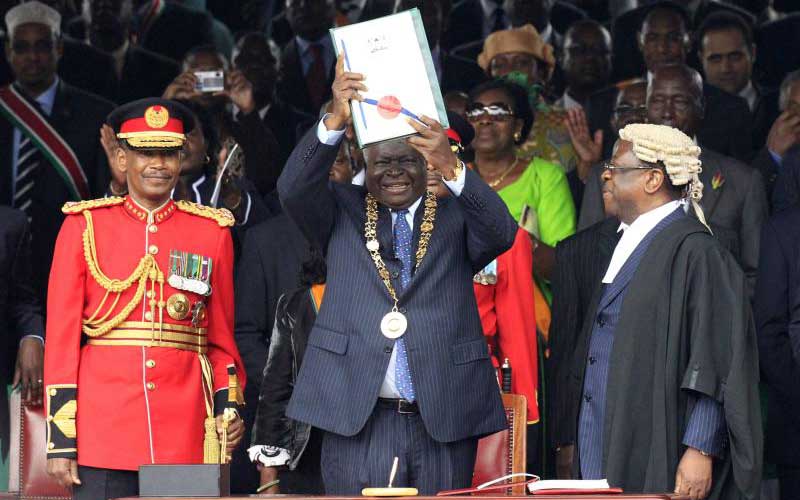

President Mwai Kibaki displays the Constitution during its promulgation at the Uhuru Park grounds in Nairobi, August 27, 2010. [File]

The preamble to the 2010 Constitution declares that we adopted and enacted it to honour those who heroically struggled to bring freedom and justice to our land and to realise “the aspirations of all Kenyans for a government based on the essential values of human rights, equality, freedom, democracy, social justice and the rule of law”.