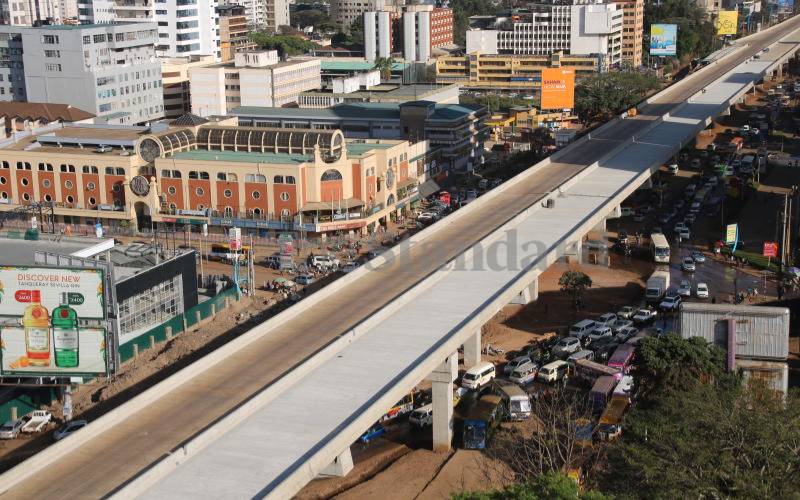

The government and the private sector have in recent years implemented or are in the process of implementing several mega infrastructure projects. They include the Konza Technology City, LAPPSET, railway projects (Standard Gauge Railway, Metre Gauge Railway rehabilitation), port projects (Mombasa, Lamu and Kisumu), shipyards, road projects, Nairobi Expressway project, airports, Pinnacle Towers, energy and power-related projects and water projects.

Most or all of these involve large overhead capital and lumpy investments whose contribution to the economy cannot be gainsaid. Infrastructure development is an important precedent to meaningful economic growth and expansion of trade and hence, Kenya is on the right trajectory.