×

The Standard e-Paper

Fearless, Trusted News

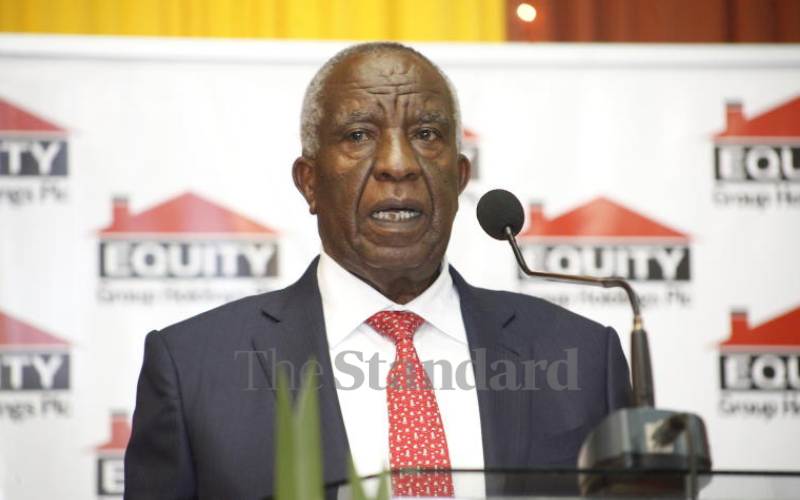

Businessman Peter Munga. [Courtesy]

One morning on May 9, 2016, two months after Peter Munga had executed his controversial “Manowari Project” that left Mauritian insurance policyholders Sh5.5 billion poorer, the billionaire businessman met a visitor from the island nation.