For six months, Kenyan banks have been like Atlas- the god in Greek mythology who carried the world on his shoulders.

They have strenuously held aloft an ailing economy, forestalling what would otherwise have been a financial meltdown.

But now, just as the late American writer Ayn Rand put it that “Atlas shrugged,” banks too have started buckling under the weight of a flaccid economy.

Profits are plummeting. Return on equity - the percentage of what shareholders receive for every shilling they have invested - has shrunk by over a third.

Equity Bank, NCBA and Standard Chartered recalled their dividends for the financial year ending 2019. KCB Bank for its part cancelled its interim dividends in the first half of the year.

The average share price of select Kenyan banks has fallen 31.6 per cent year-to-date as of October 27 compared to a drop of eight per cent for the rest of frontier banks’ universe, according to a study by EFG Hermes, an investment bank.

As a result, Kenyan banks’ price-to-book (p/b) ratio, which is used to compare a firm’s market capitalisation at the stock market to its book value, dropped to a historic low 0.7, meaning the stocks are trading for less than the value of their assets.

This is in contrast to an average p/b ratio of 1.4 in the 2014 financial year to 2019.

But it is not just shareholders’ earnings that are being sacrificed, employees too are being offloaded as banks seek to stay afloat through financial turbulence that is expected to carry on into the next year.

Standard Chartered is reported to have put some 200 employees on the chopping board.

NCBA, the third-largest bank by market size, has also communicated to its employees that it will be laying off an unspecified number of employees by the end of the year.

Reorganising NCBA’s workforce, the bank’s Managing Director John Gachora noted, is meant to protect the future of the company.

He said while it was the intention of the bank to retain all staff from the combined entities of NIC and CBA, this has been disrupted by the pandemic.

“We have had to defer our plans to scale our branch network and have taken unprecedented steps to support our customers in weathering this storm through loan moratoriums and fee waivers,” said Mr Gachora.

He noted that the recovery from the blow of the pandemic, which has seen millions lose jobs, will be slow.

“There are businesses that may never re-open and many of our customers will require support for a longer period to come.”

But Ronak Gadhia, director - sub-Saharan banks at EFG Hermes, reckons the restructuring at NCBA is primarily due to elimination of duplicated roles following the merger between the two banks.

The current struggles cut across the banking sector.

KCB Group Chief Executive Joshua Oigara confirmed to Financial Standard the lender also plans to undertake a reduction in the staff count, beginning next year.

“Review of the organisation is something we will do,” said Mr Oigara in an interview, noting that with a lot of transactions being digitised, it is inevitable that there will be some reorganisations in employment for most banks.

“This is a global development,” added Oigara.

KCB and Equity, two the of the country’s largest lenders, last week released their financial results for the third quarter of 2020.

Their performance serves as a foreword to what Oigara describes as “a year of survival.”

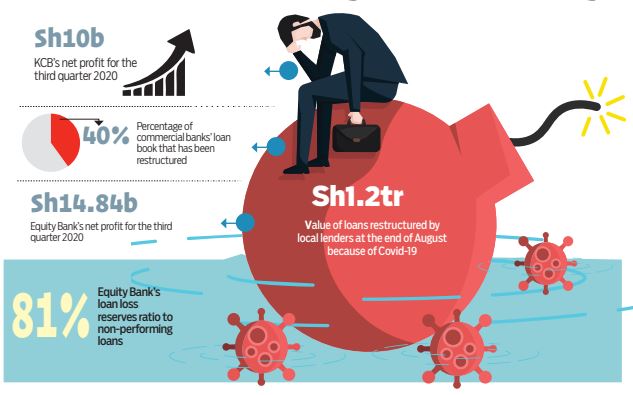

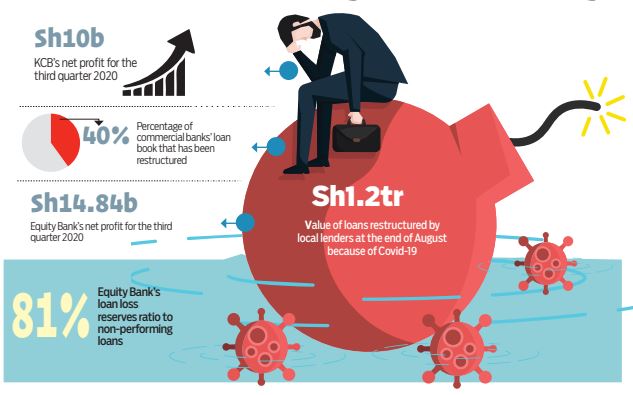

He reckons that a net profit of Sh10 billion by KCB reflects a sterling performance amidst an economic crisis.

Nonetheless, the pandemic continued to put a strain on the two lenders’ bottom lines.

Their net profits have declined sharply. KCB’s profit after tax has fallen 43 per cent from Sh19 billion in September last year.

Equity’s profit dropped by 14 per cent to Sh14.8 billion in the period under review.

In pre-Covid times, headlines would be on how, for two successive quarters, Equity has posted better results than its closest rival KCB.

If it weren’t for the Covid-19 pandemic, the two banks’ profits would be fatter and their shares at the Nairobi Securities Exchange (NSE) would be moving like hotcakes.

Central Bank of Kenya Governor Patrick Njoroge agrees that banks took a hit from these gestures.

“It was not a free lunch,” said Njoroge in his post-Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) briefing in September, noting that banks have posted reduced profits even as return on equity has significantly gone down.

“But it has indicated a change in the attitude of the banks, where they are working with the customer,” explained Njoroge, describing banks as “wonders” that need to be “appreciated.”

The Jubilee administration, faced with what the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Health Organisation (WHO) called the false dilemma between lives and livelihoods, launched a two-pronged attack against the pandemic’s health and economic impacts.

Like many others around the world, the Kenyan government moved swiftly to curb the spread of the coronavirus disease. President Uhuru Kenyatta announced the closure of schools, pubs, churches and restaurants.

All social and public gatherings were prohibited; the movement into and out of certain counties was restricted and a dusk-to-dawn curfew put in place.

These containment measures aimed at containing the spread of the virus, unfortunately also curtailed the spread of money. Economic activities drastically reduced.

Tens of thousands of businesses were shut down. Millions of workers were either fired or furloughed.

Suddenly, most of the individuals and firms that were servicing loans could not repay them.

As part of measures instituted to avert an economic crisis CBK struck a deal with banks to reschedule loans for these distressed borrowers.

This would give them some breathing space in the repayment schedule. Loans valued at Sh1.12 trillion had been restructured by the end of August, representing nearly 40 per cent of commercial banks’ loan book.

Although the restructured loans were not categorised as non-performing loans (NPLs) - loans that had not been serviced for more than three months - they were astronomical.

The new international financial reporting standards that came after the 2008 financial crisis were forward-looking. They were intended to prevent bank failures.

As a result, banks were required to set some money aside for possible defaults, not just defaults. This ate into their profits.

KCB’s loan loss provision increased more than three times to Sh20 billion by September this year compared to Sh5.8 billion in the first nine months last year.

The largest bank by asset size restructured loans worth Sh105 billion, close to a fifth of its loan book.

Equity Bank, now the most profitable bank in the country, saw its loan loss provision increase almost eight-fold to Sh14.7 billion in the period under review from Sh1.9 billion in the third quarter of last year. By the end first half of this year, Equity Bank had the highest regulatory coverage ratio with the loan loss reserves to non-performing loans (NPLs) of 81 per cent. NPLs, or bad loans, are those which have not been serviced for more than three months.

This means that should borrowers have difficulties paying these loans, Equity is likely to lose only 19 per cent. KCB’s loan loss reserves to NPLs was at 75 per cent, while Co-operative Bank’s was at 66 per cent. However, Equity has the highest exposure to micro, small and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs) at 63 per cent, noted Christos Theofilou, a senior analyst at Moodys, a credit rating agency.

MSMEs, together with sectors such as hospitality, tourism, and real estate, have been hit the hardest by the pandemic.

Equity had provided loan repayment accommodation and rescheduling for up to 45 per cent of the customers whose cashflows had been negatively impacted by the containment measures.

Banks were also not going to charge any fees for the restructuring of these loans.

Moreover, as a means to discourage the use of notes and coins, banks waived fees for all mobile banking transactions for three months to June.

CBK extended this emergency measure, which including waiving fees on transfer of sums of Sh1,000 and below on mobile phones to the end of the year.

For banks, the waiver of restructuring fees and mobile banking transactions was reflected in a drop in non-funded income, though an increase in interest income might have offset it.

[email protected]

The Standard Group Plc is a multi-media organization with investments in media

platforms spanning newspaper print operations, television, radio broadcasting,

digital and online services. The Standard Group is recognized as a leading

multi-media house in Kenya with a key influence in matters of national and

international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a multi-media organization with investments in media

platforms spanning newspaper print operations, television, radio broadcasting,

digital and online services. The Standard Group is recognized as a leading

multi-media house in Kenya with a key influence in matters of national and

international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a multi-media organization with investments in media

platforms spanning newspaper print operations, television, radio broadcasting,

digital and online services. The Standard Group is recognized as a leading

multi-media house in Kenya with a key influence in matters of national and

international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a multi-media organization with investments in media

platforms spanning newspaper print operations, television, radio broadcasting,

digital and online services. The Standard Group is recognized as a leading

multi-media house in Kenya with a key influence in matters of national and

international interest.