×

The Standard e-Paper

Join Thousands Daily

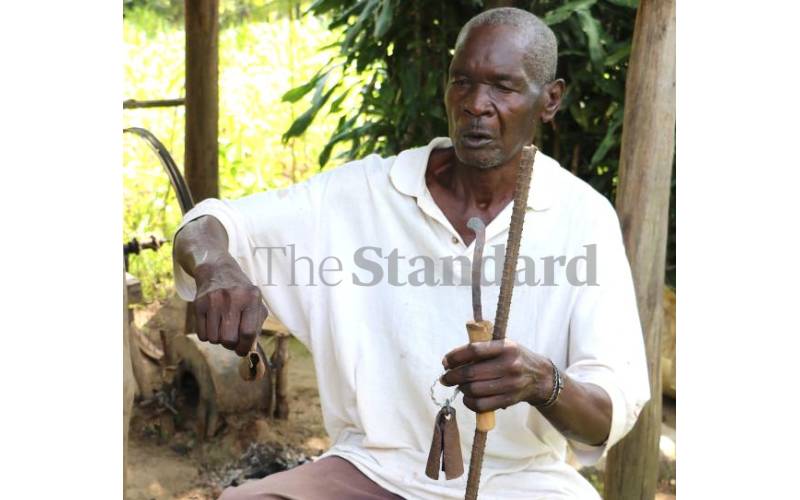

It is rare to meet a blacksmith or even spot a blacksmith’s shop in the Western region.

A blacksmith’s job entails smelting iron and creating unique tools. In the past, blacksmiths were adored for their specialised skills and ability to forge iron tools and weapons and the trade was highly valued.