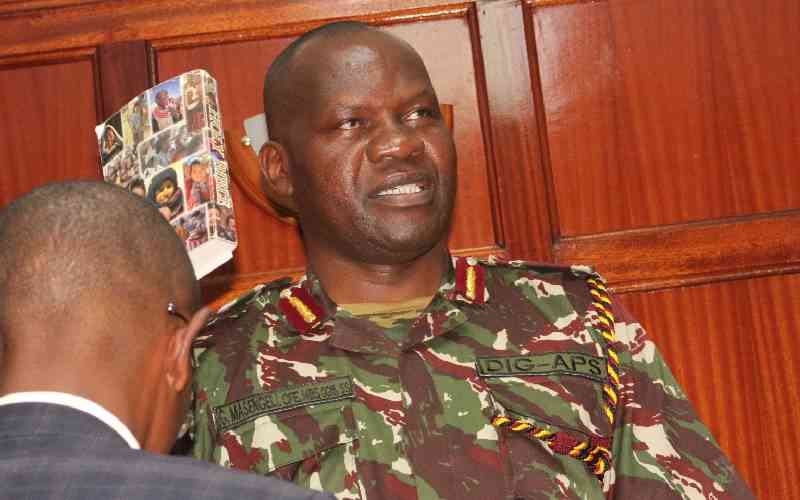

Former acting Inspector General of Police Gilbert Masengeli's travails this week made me recall some regrettable moments of Kenya's history in relation to police chiefs' contempt of court.

Unfortunately, people who lived amid those times have refused to record their memoirs so that Kenyans can know and appreciate why we cannot dare revert to that dark Kenya. On April 6th, 1987, police arrested one Stephen Mbaraka Karanja, for allegedly being involved in some criminal act. His wife, Naomi Waithera instructed Obadiah Ngwiri, a diligent criminal lawyer famous for handling pro-bono cases.