While the elite of Nairobi tussle over prime city property to put up concrete towers, majority of Kenyans continue to build using mud and cow dung.

And while the cost of housing in the city keeps on rising, sparking debates among industry players on possible overpricing, many of the country’s citizens have little to invest on houses.

Government data shows that in 27 of the 47 counties, the main walling material for houses is mud and cow dung.

It is a telling statistic that George King’oriah, a real estate and land economics expert, puts down to three factors.

One is poverty. “Say every person wants to live in a prestigious stone-walled house. Where do they get the money to buy the materials and build?” he says.

The 2020 Comprehensive Poverty Report by the Kenya National Bureau of Statistics (KNBS) indicated that 15.9 million out of 44.2 million Kenyans are poor.

It defined poverty as “an adult earning less than Sh3,252 in rural areas and Sh5,995 monthly in urban areas”.

The second factor, according to Prof King’oriah, is the general way of human behaviour that reaches out for what is readily available in their environments if it is usable.

If a building material is provided by the environment naturally, then communities go for it.

“When there is so much grass around, why do you go around buying stones?” asks the University of Nairobi lecturer, citing Garissa, Wajir

and Mandera counties that mainly use grass and reeds walling.

In central and eastern Kenya counties bordering Mt Kenya, timber is the predominant material for building.

In Embu, Makueni, Machakos and Makueni, the communities mostly use bricks to build, the material easy to manufacture in the environment.

Tom Oketch, who chairs the Institution of Construction Project Managers of Kenya, agrees with King’oriah.

In Mombasa, for example, the presence of lime makes it a key walling material for the locals.

Stay informed. Subscribe to our newsletter

“So why one would struggle to look for stones when lime is outside their door?” he asks.

What is not locally available will be expensive to purchase and to ferry to construction sites.

Many people in Coast use lime, which is easily available and easy to excavate, but not everybody can afford to hire people to go and mine it. So even in the same region, you will find mud walls, says Dr Oketch.

The third influencing factor, on building material is culture, King’oriah says.

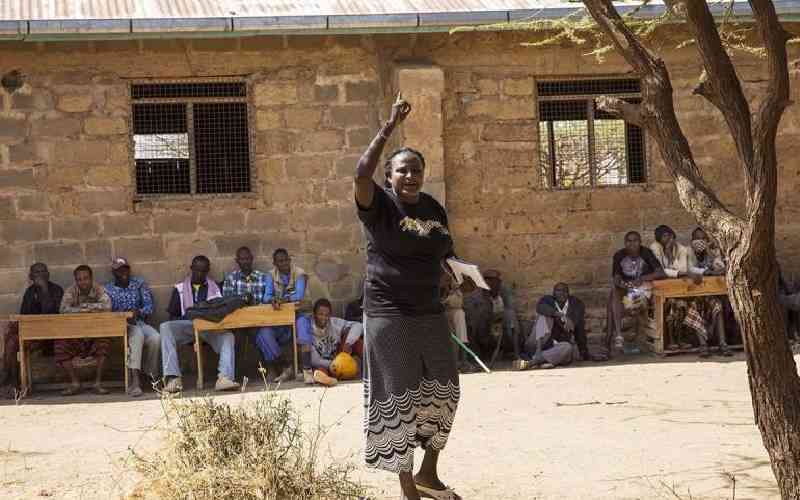

Most communities are not yet acquainted with modern architecture and they do not see the need to, as they are comfortably snuggled in a tradition that affords them comfort.

What would make the Maasai ditch their famous manyatta for a skyscraper in the middle of a sprawling Kenyan savannah?

“Stone housing and all the architectural and design improvements are an idea of nobility coined by the white man. Some of these communities do not care about noble housing,” says King’oriah.

“There is an attitude hard to change, and with good reason. These people are comfortable living in their traditional shelters.”

It is like fashion, he says; its adoption is gradual and without an assurance that the whole population will embrace it. And if they will, then probably in phases.

Oketch says roles associated with tradition mean that it is hard to adopt a new way of doing things in communities that remain deeply rooted in their cultural beliefs.

“Cultural considerations have a lot to do with people’s building patterns. People want to maintain a culture that comes through rites,” he says.

“In some parts of Western region, for example, at a certain age, a boy is required to have a hut called simba. That is a structure which goes up within a day. In that respect, people have to go for the most readily available material.

“If there is a death in the family and someone did not have the house, the house must come up immediately. This is a practice that is hard to do away with, and such houses are built using materials that can be sourced without a big hassle.”

He adds a fourth reason why people build using the materials they do: the climate.

“Climatic conditions influence the choice of materials. You find that in regions where it is cold, they will go the timber way. In hot regions, they can even use grass.”

It explains why the mountain regions - bar the fact that trees are commonly available - use timber for their walls. In search of warmth.

Coastal temperatures also influence their roofing patterns, and while a majority use iron sheets, many others use makuti, especially in recreation joints, even when they can afford alternative forms of roofing, mainly because that kind of roofing affords a much-needed coolness in the houses.

“A mabati roof could roast the people inside,” remarks Oketch.

In terms of technology, people want to use the technology that they are familiar with - what they know how to use comfortably, rather than fumbling with foreign materials.

And while at it, Oketch notes, it is less economical to use permanent material. Some communities, especially nomadic ones, have to rebuild frequently and it would make no point for them to use stone walls for their structures.

Communities that use cow dung sometimes have yet another reason to do that: the dung is a preservative and acts like plaster, keeping away insects that would gnaw at the wood.

They also smear it on the floor as it also protects the people living inside the structures from possible attacks by insects.

In the KNBS data, while the walls were found to be predominantly mud and cow dung, the roofs were mainly iron sheet.

The 2019 Kenya Population and Housing Census data shows that 80.3 per cent of the households occupied dwelling units that had iron sheet as the main roofing material followed by concrete or cement at 8.2 per cent.

“The dominant material used for wall construction was mud and cow dung at 27.5 per cent followed by stone with lime or cement at 16.5 per cent,” said the report.

“Dwelling units with concrete walls accounted for 16.3 per cent of the total. The predominant floor material was concrete or cement accounting for 43.7 per cent followed by earth or sand floors at 30 per cent.”

King’oriah says the ease of using iron sheets makes it a good roofing material.

“Iron sheet material is the simplest to use in roofing, is readily available and is very efficient,” he says.

Companies that manufacture iron sheets have increased in the past few years, evidence of Kenyans’ preference for the roofing material.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.