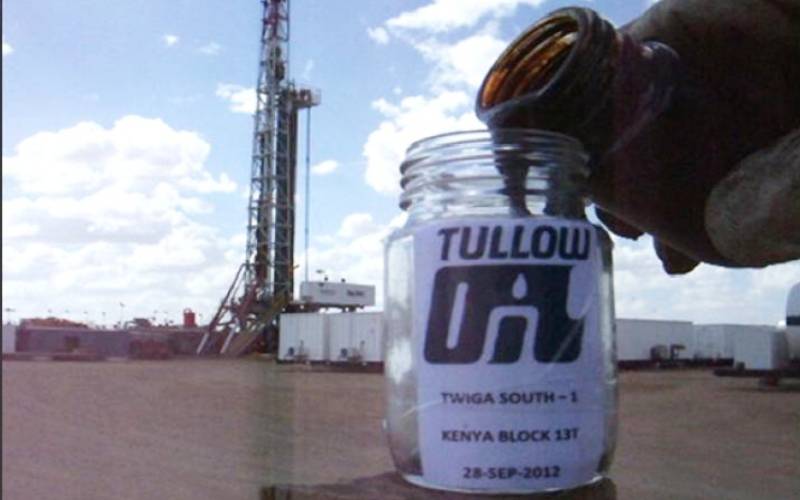

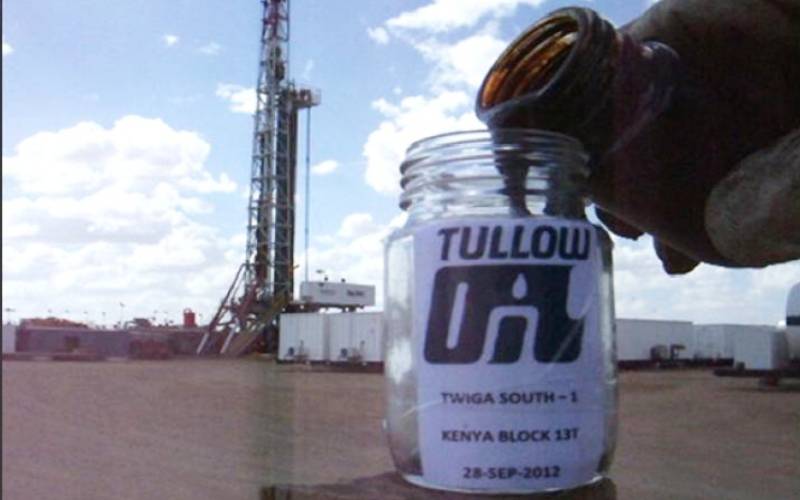

Perhaps Tullow Oil Plc, the company at the heart of Kenya’s much-hyped oil fortune, is a fraud.

Fact‑first reporting that puts you at the heart of the newsroom. Subscribe for full access.

- Unlimited access to all premium content

- Uninterrupted ad-free browsing experience

- Mobile-optimized reading experience

- Weekly Newsletters

- MPesa, Airtel Money and Cards accepted