×

The Standard e-Paper

Kenya’s Boldest Voice

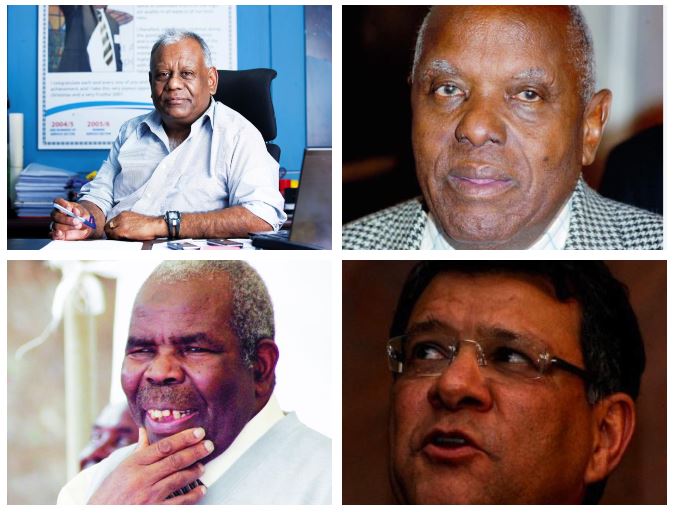

If you have been fascinated by the rags-to-riches stories of the late politician Njenga Karume and Nakumatt Supermarket’s founder Mangalal Shah, then your excitement must have been deflated.

Last week must have been a watershed moment for the two business empires that were built from scratch to splendour without succour.