×

The Standard e-Paper

Join Thousands Daily

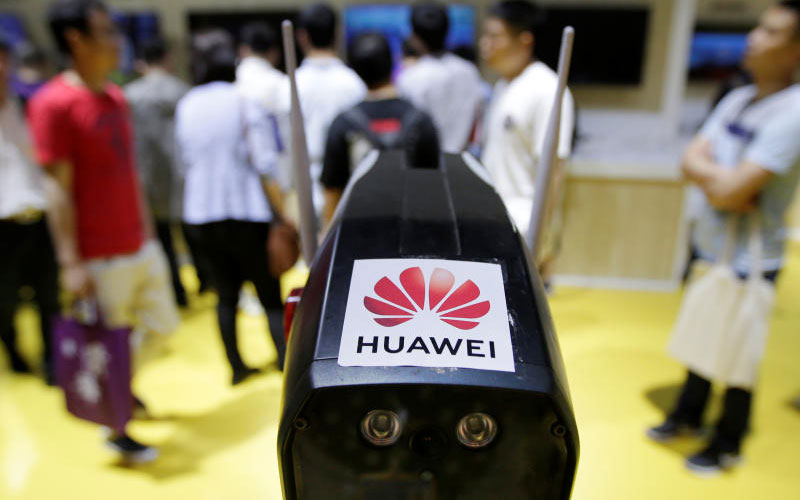

President Donald Trump last week signed an executive order whose ripples may reverberate beyond the US borders all the way to Kenya.

With one stroke of the pen, Trump declared a national emergency giving US companies legal grounding to ban information and communication technology suppliers perceived to be a security threat.