×

The Standard e-Paper

Fearless, Trusted News

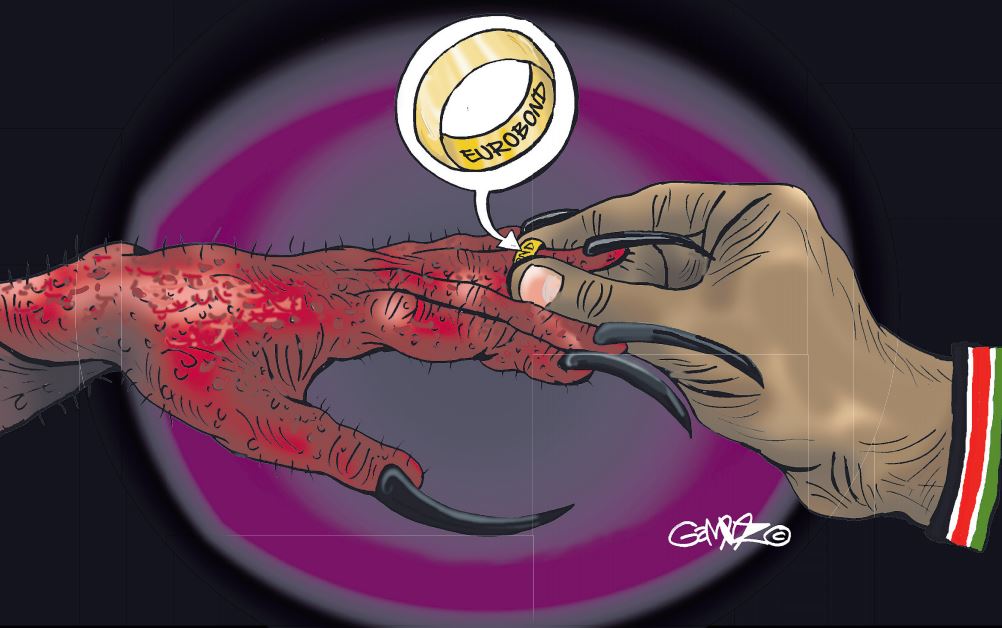

Two days from today (Tuesday), the Executive Board of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the highest decision-making organ of the Washington DC-based global lender, will make a decision that might echo through Kenya’s future.