×

The Standard e-Paper

Stay Informed, Even Offline

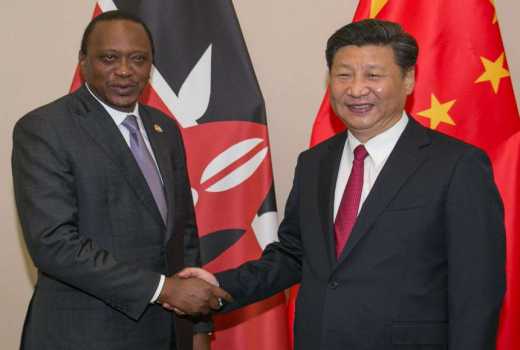

?Kenya’s trade relationship with China has been severely skewed, with the Asian nation receiving more but giving less in the last decade.

China has stretched Kenya’s hospitality, taking advantage of the country’s open-door policy to flood the market with all manner of goods. Construction machinery, building materials, used clothing, onions, tilapia, tooth picks, toilet paper - no sector is safe from the ‘Sino-invasion’.