Millions of Kenyans are stuck in one of the worst economic crises after food prices suddenly shot up leaving many staring at starvation. Prices of maize flour, milk, tomatoes, cooking oil, onions and sukumawiki (kale) — the most basic foodstuff—have risen sharply in less than two months making life unbearable for ordinary consumers who toil just to put food on the table.

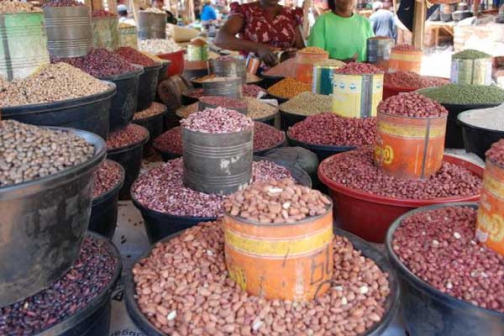

Kenya’s staple food maize is the worst hit with a gorogoro (a two-kilogramme tin) of the cereal in most rural areas trading at between Sh100 and Sh130, up from between Sh70 and Sh80 during the festive month of December. At Kibuye Open Market in Kisumu, a gorogoro of maize is going for as high as Sh130, a price last seen in 2009 when the country experienced a similar crisis in the lakeside city.