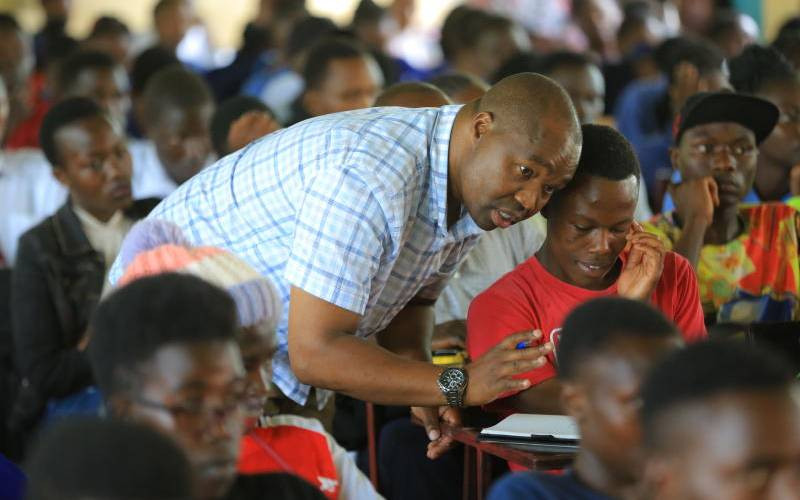

Chairperson of Technical working group on Gender Based Violence including Femicide Nancy Barasa during a stakeholder engagement at KICC , Nairobi on April 9th 2025. [Collins Oduor,Standard]

×

The Standard e-Paper

Kenya’s Boldest Voice